I am a political animal, and so cannot tear my eyes away from the ongoing saga of the US Presidential Election.

The most extraordinary (in the true sense of that word) aspect to it is that there is now a significant faction in the US willing to undermine the reputation of their own country’s electoral processes.

I have been thinking hard about how I have reacted when ‘my side’ has lost electoral contests to be certain that this is as extraordinary as it feels.

I have certainly whinged about the electoral system being unfair to my party, and whined about unfair treatment in the media, and moaned that the other side have conned people with their lies.

But I cannot recall any campaign I have been involved in where I, or those around me, tried seriously to overturn the result on the basis that the outcome was due to votes that had been cast fraudulently.

There are of course instances where people break electoral law and cast votes they should not, but it is hard to do this at scale and in ways that escape detection – each vote represents a high risk, low reward offence.

It does seem that the current US situation is a special case and that it deserves a special response.

My particular interest is in how internet platforms should respond, not because this is the most important aspect today – the response of the judiciary is of more immediate concern – but because this is where people fear that damage may be done over the longer term.

The two social media platforms that receive most of the attention when it comes to US politics – Facebook and Twitter – have both implemented measures that are quite a step change from where they were a year ago.

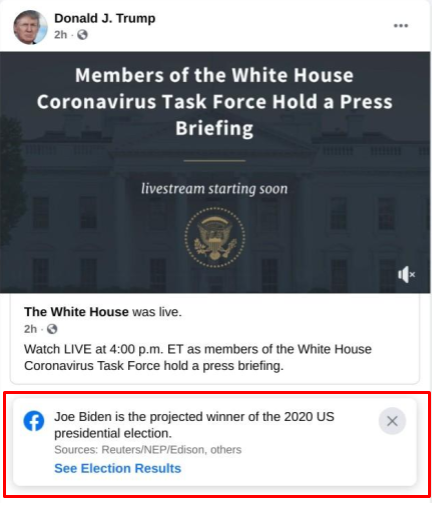

Interestingly, these measures, which involve adding labels to false election content like the one above, have already to a large degree been discounted by critics who want to see more done.

These companies are big and ugly enough not to need much sympathy but, as a former FB employee, I can relate to the ‘ignored if you do, and damned if you don’t’ spirit that they may be labouring under right now.

In this post I want to look at what more platforms might do assuming a political faction in the US continues to make attacks on their electoral system in an attempt to undermine a legitimate outcome that they don’t like.

First, a Shroud

It has become common for people to describe approaches to politics in a polarised environment as being based on faith, and closer to a religious than classically political mindset.

This similarity with religion does seem worth teasing out as a way to understand how people are seeing information about the election, and how they might respond to any interventions by platforms.

We often bandy around the phrase attributed to the late Senator Moynihan that “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts.”

I would reframe this to say that people also lay claim to their own ‘realities’ as something much more concrete than mere opinion.

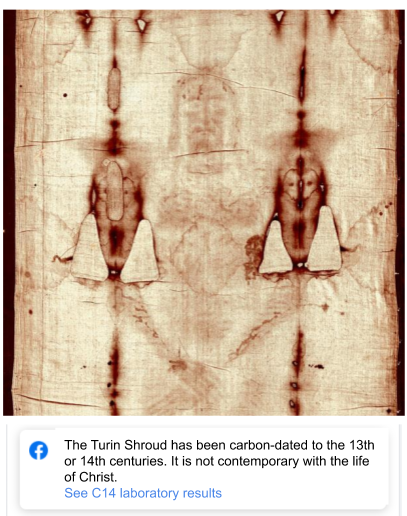

We can look at religious relics as examples of things that have become as real as anything else in this world to those who believe in them.

If we take the case of the Turin Shroud, for many millions of people around the world this was the cloth that wrapped Jesus Christ’s body.

Scientific tests have been performed that have generated facts that do not necessarily comport with the reality as known to believers in the shroud.

Bringing this back to social media, we can look at what might happen if a platform applied a factual label to content asserting that the Turin Shroud was from the time of Christ.

How do we think this label might affect people who are reading about the shroud on a social media platform?

For those who are firm believers in it, this label is unlikely to change their minds in any meaningful way – they can find many counter-arguments out there that would allow them to dismiss it, eg that the C14 sample picked up modern fibres.

But even if their opinions do not change, they may prefer not to share posts about the shroud that are labelled in a way that they think is inaccurate and derogatory to something that they believe in.

For those who are firm sceptics of the shroud, the label will be a welcome affirmation of their existing view, but they may still feel it is irresponsible of the platform to allow this content to be circulated as others are more credulous.

For those who are unsure about the shroud, the label may cause them to ask more questions, but they might still end up consuming more ‘pro-shroud’ than ‘anti-shroud’ content overall if it is more prevalent on the platform than in other places.

It will take time (and data) for the effects of the recent labelling approaches of Twitter and Facebook to be understood with any rigour, but there has been a media report suggesting there is some reduction in the sharing of labelled content on Facebook.

This would seem consistent with the hypothesis that believers may be less likely to share something that carries information undermining of their belief (while remaining the group most motivated to share it generally).

[NB the media article is dismissive of the approx 8% reduction in shares that was reported to them but other commentators see this as quite a big deal].

We can expect much more analysis of the effects of all sorts of platform policies through the election period over the next few months including testing hypotheses around the effect of factchecker labels.

Election Heretics

As we consider how platforms might evolve their approach as events unfold, we can continue to use the religious analogy.

There is an orthodox approach to elections which is that all parties involved in a contest accept the outcome and continue to support the political system whether they win or lose.

In most countries all of the major parties hold to this orthodox view even if they shout loudly about things they perceive to be unfair.

There may be some claims that the system is so flawed as to be illegitimate, but these generally come from smaller factions at the extremes of the political spectrum, as well as sometimes from overtly terrorist organisations.

What is unusual in the current US situation is that such a large faction as the Republican Party appears to be moving so far from the orthodox position of trust in the electoral process, and is now positioning itself amongst the heretics.

The danger for the country is that followers of this heresy will feel no loyalty to a system of government that they have lost faith in and that this will in turn have a wide range of negative societal consequences.

In deciding how to respond to this there is a foundational question – do you take the orthodox view that the US electoral system is fundamentally sound, or do you take the heretical view that it is irredeemably broken?

If you are in the latter camp then you will want platforms to get out of the way and do nothing to stop you evangelising your view of the world in the hope it can defeat the orthodox position.

We should be self-aware and recognise that there are times when many of us look to social media as a positive force precisely because it permits novel challenges to orthodoxy in areas where we feel this is needed.

So it is certainly not the case that we would always want platforms to favour established positions over unorthodox challenges – we are likely rather to look at this through the lens of our personal value systems.

Special Cases

There are though good reasons to treat an orthodox position on core political institutions as especially deserving of respect, even where arguments are more finely balanced on particular issues within that system.

There was an episode during the Brexit saga where the UK Supreme Court made a ruling that they believed accurately reflected UK law as set down by Parliament over the centuries.

This caused some in the pro-Brexit faction to move very aggressively against the UK Supreme Court questioning their competence and legitimacy.

This heretical challenge to an orthodoxy – that the UK legal system is a leader in terms of fairness and wisdom – risked causing lasting structural damage because of pique at one particular decision.

There is no avoiding making a choice on these matters, and I take the more orthodox position of supporting the political institutions of my country as ‘good enough’ even where I dislike particular outcomes.

I would like to see significant reforms and have been a member of a pro-reform faction throughout my political life but want to see these changes brought about by winning battles within the system rather than having them forcibly imposed after undermining the institutions of government.

It feels strange to have to assert a position like this but the times require it.

Solutions

I will look at solutions based on the assumption that we should be supporting the orthodox position that US elections are sufficiently free, and fair and do produce valid outcomes, over the heretical one that they are so corrupted that their results cannot be trusted.

If that is not your view, you may wish to look away now.

The single most important development that could happen is for high profile political leaders to renounce the heretical viewpoint and publicly acknowledge the correctness of the orthodox position.

It is important not to lose sight of this as being the optimal outcome, and that absent this leadership any other measures are lesser forms of compensation.

Many commentators are saying this but it bears repeating that the choices made by the current US President and his supporters are most significant here.

It is clear that they fear schism in their movement, and anyone who has worked in politics will understand just how fearful parties are of splits that could leave them out of power for years.

But if the alternative to schism is for the entire party to adopt a heretical creed that is anathema to its core values then sometimes this has to take its course.

By way of reassurance to the politicians, history also shows us that schismatics from major political groups often end up being fewer in number than feared and have a very short half-life.

The most drastic step that platforms could take, and one that seems to be picking up some support, is to ban the use of their services by leading heretics if they will not recant.

If all you are concerned about is limiting the spread of the heretical views then this is superficially attractive.

The strongest counter-argument is that it would in effect be allowing one heresy – that against the electoral system – to beget another heresy – as platforms turn away from protecting diverse political speech.

You could construct an argument as to why the threat posed by leaders of this heresy is so serious that a ban would be justified, but to the extent that the speech expresses a political viewpoint, however wrong-headed or downright deceitful, prohibition feels inconsistent with free expression principles.

This calculus would change if leaders move towards speech that incites violence and there will different views on when this becomes true especially in respect of implicit or ‘dog whistle’ language..

If leaders confine themselves to false political claims and are not banned, then we need to look at how platforms might use different ‘treatments’ around the heretical content.

These treatments typically involve some mixture of

- a) visible labelling,

- b) friction when users access and/or share the content,

- c) different weighting in distribution algorithms,

- d) exclusion from discovery mechanisms.

Platform treatment of content from heretical leaders at the moment largely involves carefully worded visible labels with reduced distribution in some cases.

Platforms may wish to do more to reduce distribution and remove content from discovery mechanisms where they have a good faith belief that it is harmful to their users.

These mechanisms do not necessarily limit someone’s ‘right to speak’ on a platform but they will upset those who feel they have a ‘right to reach’.

For platforms to consider these reach-reducing actions, they would need to have made a value judgement – that the heretical position that US elections are untrustworthy is actively harmful.

If they do make that determination and are transparent about this, then they have a reasonable basis to disfavour that content (and would arguably be negligent if they do not act).

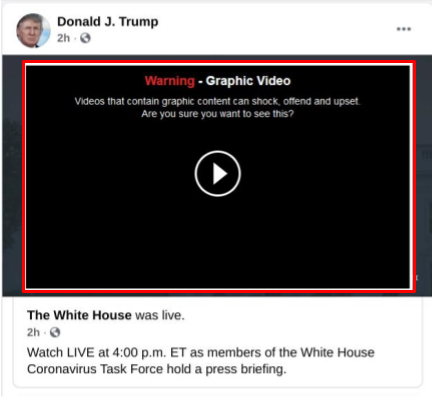

Even more impactful might be a shift from simple labelling to placing warnings over content that require users to take actions before seeing.

These are known as ‘interstitials’ in the business and are used by Facebook for content that is gory enough to upset some people while not bad enough to breach their rules.

Platforms could apply warning screens to false election content that put the facts in your face to varying degrees.

In this mockup, I have added the Violent content warning screen to a video making false claims about the election though in practice the text on this would be tailored to explain that there is a problem with election claims.

This is more in your face than the informational warning underneath the content but the user would get to the content with a simple click-through.

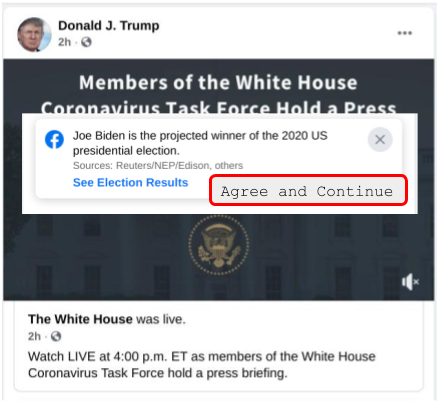

This final mockup is an even more direct treatment where the information about the election outcome is put right on top of the content and the user is asked to acknowledge this in some way before proceeding.

There are other models like this within platform content review systems where you are asked to read the terms of service and commit to respecting them when you have posted violating content.

The requirement to acknowledge the facts can be scaled up or down with more direct or indirect language in the explanatory text, and on the button.

Some viewers will feel this is excessively aggressive and coercive – to be required to recognise something you disagree with before proceeding to content you want – and heretical content producers may feel it is not worth using a platform that imposes these requirements.

In ordinary times, these complaints might tip the balance against this level of intervention, but it is worth considering for extraordinary situations.

Limiting damage to the fabric of the democracy of a country is one such situation, but we also currently have to consider how to respond to anti-vaccination content in the context of the global pandemic.

With vaccination there is also an orthodox view – we can trust that pharmaceutical companies, regulators and doctors are acting in good faith and delivering safe products – and a heretical one – various kinds of fraud are being perpetrated on us by a malign establishment.

If you believe, as I do, that it is important to maximise take-up of the new vaccines, then we need to consider what actions would be most likely to limit the spread of the heretical viewpoint.

In this struggle, simple warning labels on content making false claims about vaccines may not be sufficient.

But trying to ban all those who make anti-vaccination claims may feel inconsistent with free expression principles.

Working to reduce the distribution of false claims and reduce their discoverability are helpful but may have limited impact where people are pushing content to each other more directly.

This may be another scenario where the most appropriate treatment would be to overlay factual material onto false claims and require acknowledgement before they can be viewed.

A Closing Prayer

It is hard right now to avoid being pulled into a vortex of anger where everyone feels slighted by those on the ‘other side’.

This leads us into the terrible trap of thinking that ‘my enemy’s enemy is my friend’.

In reality, some of the people who share your values, and should be your friends, happen to be sitting in the enemy camp.

And you may have welcomed others into your camp, to swell your numbers in a tough fight, without stopping to find out if you really are on the same side.

Social media certainly can contribute to the vortex of anger and we have to recognise and be honest about the potential risks.

But it can also allow us to reshuffle our social decks, and get out of our mutually hostile encampments, if we want this and work at it.

I still have enough optimism in the tank to believe that, while there may be some hard reckonings along the way, we can arrive at a place where :-

Science and technology would be used as though, like the Sabbath, they had been made for man, not (as at present and still more so in the Brave New World) as though man were to be adapted and enslaved to them.

Aldous Huxley, foreword to 1946 edition of ‘Brave New World’.