There is a lot happening at the moment to focus minds on the subject online content moderation.

The EU has a new law coming into force called the Digital Services Act that creates significant new powers for government authorities to tell platforms how to moderate content.

The UK is working on another law called the Online Safety Bill which will give its telecoms regulator, Ofcom, a major role overseeing a range of online services.

And a number of other countries around the world have expressed their interest in regulating the way in which platforms manage a wide range of content.

On the industry side, the arrival of a new owner at Twitter is shining a fresh spotlight on many aspects of content moderation that companies have been wrangling with for years.

As this is a hot debate, I thought it might be helpful to put a few notes together describing the various forces that act as moderators of online content.

This is intended to support the public and legislative debate by showing how different forces can all come to bear and shape the environment for online speech.

NB if you like the podcast format then you can listen to Nicklas Lundblad and I discussing this model in the latest episode of our Regulate Tech podcast.

In this post, I am thinking of content moderation in the context of services that host various types of content for access by some kind of wider audience.

This model does not apply to instant messaging services that do not host content as such but simply move it from one device to another (there may be some temporary storage until a message is delivered but this is very different from website hosting).

It is hard to define a particular size of audience that brings hosted content into scope but questions may be raised about moderation whenever content can be accessed beyond a small group of people such as a single family or close sports team.

Once content is on display to a reasonable number of people then the conditions are there for someone to object to it in some way.

This will typically be expressed as a request that the content be removed from the hosting service with reasons why this is desirable and/or necessary.

Someone then needs to make a decision whether to accede to that request and remove the content or disagree with it and allow the content to remain available.

Some complaints may seek outcomes other than full removal such as restricting access to the content according to some criteria, for example by age or location, and these also require a decision to be made.

So who are potential decision makers and what is influencing the choices they make?

PART 1 – THE MODERATORS

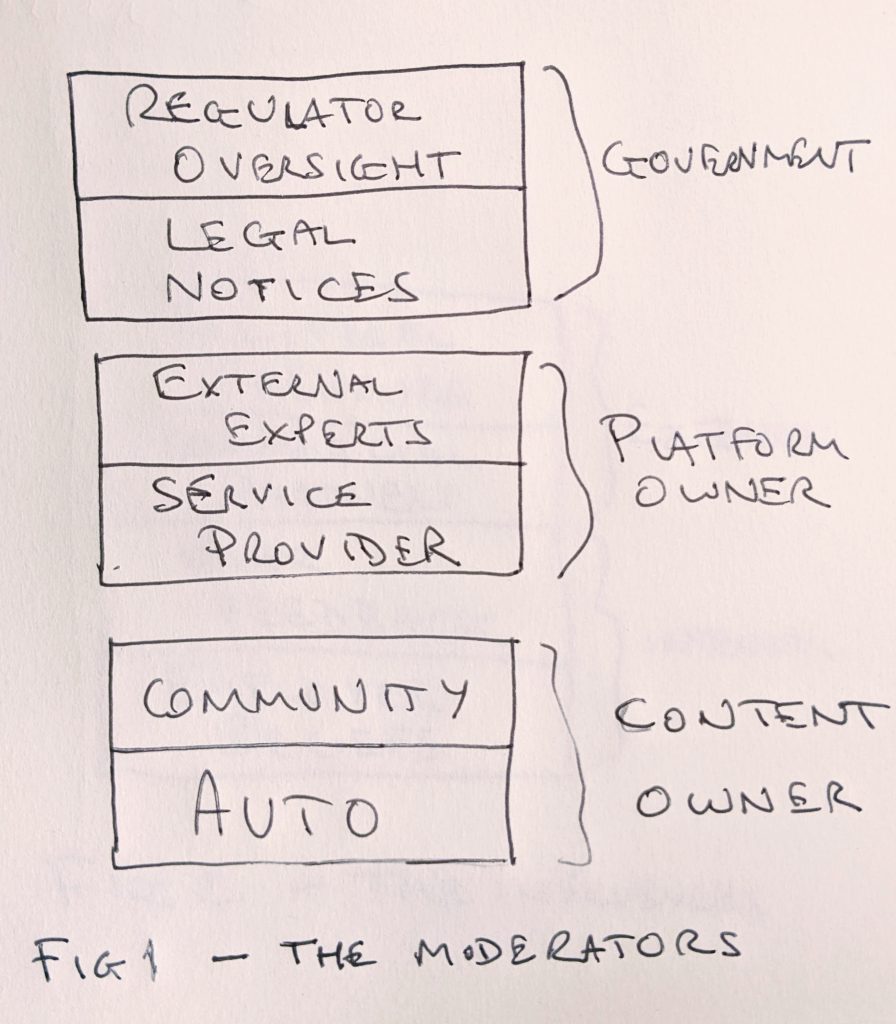

In this model, the key players fall into three groups – A – Content Owners, B – Platform Owners, and C – Governments.

A – CONTENT OWNER MODERATION

We can expect content owner moderation to be responsible for the greatest number of decisions in many online contexts but this is often overlooked in debates around the role of platforms and regulators.

A1 – AUTO

The first flavour of content owner moderation is when decisions are made by the content owner themselves – ‘auto’ is used here in the sense of ‘autobiography’ not ‘automated’.

We post content and we change our minds and we take it down again. This may be as a result of negative feedback or just because we have second thoughts.

This is the default mode for user-owned websites like blogs where the owner decides whether or not to remove their own content.

It is also the default mode for the core content of traditional news media sites where the journalists and editors decide whether to maintain or withdraw a story they have published.

There may be pressure on a blogger or news media site from external forces and we shall look at some of these later but if they exclusively have the technical capability to remove content then the moderation decision is ultimately theirs to take.

Where the content is hosted by a third party then other decision makers can be more powerful but the individual user may still be the most significant actor when it comes to their own content.

NB comments on blogs or news media sites fall under a different regime, I am talking about the core content here.

For the strongest free speech advocates this is generally the preferred mode – posters of content should have the power to decide whether to keep something up or take it down and nobody should be able to ‘censor’ them.

And it remains a viable model for someone who is responsible for their entire publishing stack, for example running blogging software on their own server and taking full responsibility for connecting this to the wider internet.

A2 – COMMUNITY

This is where a community gets to decide whether content should stay up or come down in a particular online space that is deemed to be ‘owned’ by that community.

The power to remove content may be vested in every member of the community or in a smaller subset of members who have administrator rights.

There are a variety of models for deciding who gets to be an administrator of community spaces and for the community to support or challenge their decisions.

This model is found within services that provide group spaces and has especially been associated with Reddit subreddits and Facebook Groups.

There is also a long tradition of this kind of moderation in the various bulletin boards and other online fora that in some cases predate the internet.

The key challenge for this kind of moderation is how far it can be scaled given the need for a coherent set of norms for a group to feel comfortable following them – the more people in a group, the harder it is to find consensus.

As with Auto Moderation, there may be a higher power able to take actions over the heads of the community where it is hosted on a platform that has its own moderation tools in place.

B – PLATFORM OWNER MODERATION

For a platform owner, auto and community moderation are actually highly desirable as they tend to be a) cheaper, and b) make for happier users.

The rational position for a platform to take is to rely on these modes as far they can and at least in their early days many services can remain quite hands-off.

But legal liability and reputational risks mean that this reliance on community moderation cannot be unlimited and at some point platforms will need to step in and introduce their own moderation systems in some form.

B1 – SERVICE PROVIDER

This is perhaps the model that most commonly comes to mind when people talk about online content moderation – the service provider creates rules and employs people, either in house or as contractors, to enforce those rules.

Some services have tried to manage without doing much moderation either because they are philosophically opposed to central control or because they do not want to incur the costs of doing this work, or both.

We generally see that demands for intervention increase when services grow and become more mainstream because of a range of pressures that I will outline below.

Once a service starts to moderate at scale then we often see criticisms from people whose content has been removed claiming that the moderation is flawed in some way.

The status quo for most of the major online services is that they have put in place significant moderation teams and face frequent criticism about how they are managing various types of content.

It is sometimes claimed that if both sides of an argument are equally upset then you must be doing something right but this does not feel like the optimal place to be for a service provider.

They rather see their critics forming up from across the political spectrum creating a head of steam for more external control of their decision-making.

One way for platforms to try and head off criticism about their moderation policies and practices is to bring external parties into the process and we will look at this next.

B2 – EXTERNAL EXPERTS

Platforms have long looked to external experts to support their content moderation efforts in one guise or another.

A very high profile example of this is the Oversight Board that Facebook, now Meta, established in 2020.

This was an explicit attempt by the company to detoxify at least some of their content moderation decision-making by having independent experts analyse and opine on their actions.

We should also recognise that an ecosystem of subject matter specialists has built up over many years who are called upon by platforms either individually or as part of a non-governmental organisation.

While this is less high profile than the Oversight Board, there are long-standing mechanisms for platforms to seek external input in areas such as child safety, counter-terrorism and misinformation.

In some instances decisions are effectively out-sourced to these external experts, for example with Meta’s Third-Party Fact-Checking Program.

But however responsive services are to their external experts, their roles are at the discretion of the platform owners and so this is more properly considered an extension of platform decision-making rather than wholly outside of it.

Interestingly, the new legislation from the EU, the Digital Services Act, starts to develop a statutory framework for these external parties by defining ‘trusted flaggers’ whose reports will have to be prioritised by platforms.

C – GOVERNMENT MODERATION

The position of governments in respect of online content moderation varies widely between different kinds of regimes around the world.

Some governments have a culture of tight control of the media and of the speech of their citizens and see it is their right and a natural development for them to extend this control to new online spaces

Others are much more reluctant to interfere beyond requiring some basic legal compliance and would prefer to see online spaces manage themselves as far as is possible.

C1 – LEGAL NOTICES

Most countries define some forms of speech as illegal and have created mechanisms in law to require everyone to help limit the illegal speech or risk facing criminal or civil sanctions.

This ranges from content like child sexual abuse imagery, which is criminalised in almost every country, through to copyright material shared without permission, which is a civil offence in most countries.

There are different legal regimes around the world spelling out what platforms need to do to manage illegal content but in most cases there is an expectation that platforms will have to take action when notified about illegality.

These notices can then form an important part of platform content moderation systems whether or not the platform agrees with what is being prohibited.

Notices will typically refer to individual content items so they are not likely to be high volume but they may impact on important and high profile content.

And where there is a significant number of notices about a particular content type then a platform may change its moderation approach to manage its exposure to risk, for example implementing automated filters.

The issuers of notices will commonly be organisations, for example rightsholders, and government agencies, for example the Police, but may also include individuals, for example in cases of alleged defamation.

The German government attempted to make it easier for individuals to issue notices in their Network Enforcement Act, supercharging this existing regime but not yet moving to full regulatory oversight of platforms.

The latest wave of legislation from the EU and UK takes government intervention to another level beyond just considering platform responses to illegal content notices.

C2 – REGULATOR OVERSIGHT

If a government has formed the view that platforms are making poor decisions about content moderation and that this is having a serious negative impact on their citizens then they have to consider the best way to intervene.

One approach is to define more speech as illegal and to be very robust in insisting that platforms respond to notices about that speech, and some countries continue to follow this model.

The Content Restrictions of the Facebook Transparency Report provides a window into how this plays out in different parts of the world with some countries sending in thousands of removal requests each month.

But we are now seeing some countries, notably the EU and UK, take a different approach by creating new mechanisms where online services will be placed under the formal supervision of a government regulator.

How services handle notices of illegal content will form part of these new regulatory regimes but regulators will require platforms to do much more, for example carrying out risk assessments and providing data to regulators and researchers.

We have yet to see how these oversight mechanisms will actually impact on content moderation as they are very much ‘in development’ as I write, but it seems likely that they will represent a major step change in this area.

PART 2 – THE INFLUENCES

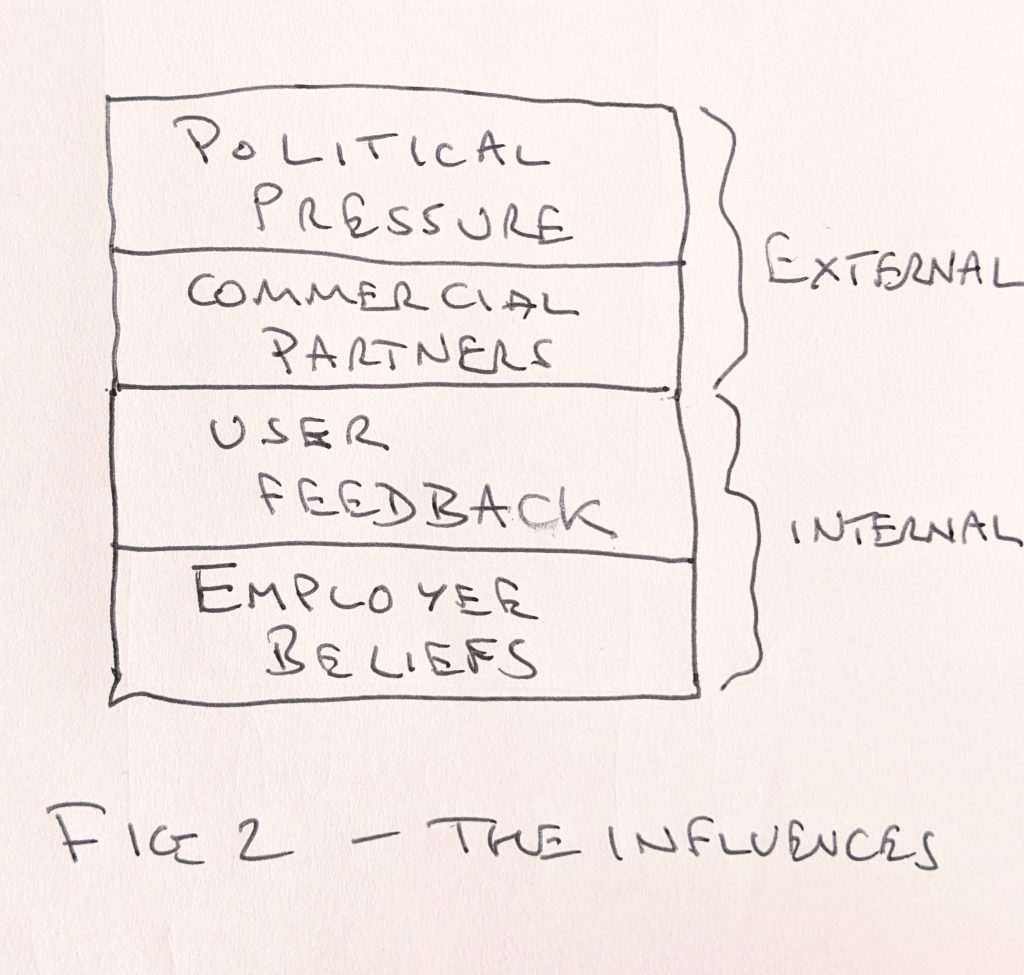

After looking at who is responsible for content moderation it is worth spending a little time considering the forces that influence the policies and processes of online services.

Again, this is multi-dimensional and several of these factors may be in play for particular content decisions with anything very high profile and controversial likely to generate pressure from all four quarters.

EMPLOYEE BELIEFS

Allegations of employee bias often become a hot topic when people claim that the political views of the staff of an online service are a factor in decisions about their content.

But more fundamentally, the whole approach to policies and content moderation will be shaped by the world view of a company’s leadership – it would be inhuman for this to be otherwise.

The class of people from which the founders of most US platforms is drawn is one which prizes freedom of expression and is hostile to government censorship.

This tends to make them reluctant content moderators who would much prefer not to have to intervene as a general matter.

It is also no secret that the personal views of tech company employees are often tilted towards the left of the political spectrum which may leave them feeling uncomfortable about some kinds of speech created by their users.

In my experience it is a dramatic over-simplification to suggest that employees act on their own biases to ban speech they disagree with but there is instead an ongoing tension between their position on free expression generally and on specific kinds of objectionable content.

This tension will inevitably have some impact on decisions being made as part of a broader mix of factors including those set out below.

The classic free speech position – we hate what you say but we defend your right to say it – reflects the norms of liberal democracies like the US and ther will be other norms shaping decisions at services whose leadership has grown up in different political contexts.

USER FEEDBACK

The influence of users on approaches to moderation may be much less obvious than for the other forces I describe and so it may be assumed, incorrectly, that it is trivial.

Their impact can be found at both the aggregate and the individual level.

Services, at least well-run ones, will collect huge amounts of data about users reporting content and they will survey both reporters and reported parties to see how they feel about how their experiences.

These data will be an important part of the decision-making process when a change is proposed to content policies or the content reporting systems.

As well as the aggregate measures, individual users can sometimes create a powerful voice for themselves that moves platforms.

The typical mode for them to build that voice is by amplifying their issue in the media and/or getting it taken up by politicians, celebrities, or influential commercial players.

This is not to overstate the power of a single user relative to a major platform but high profile campaigns against services are a common occurrence that bears on their decision-making.

COMMERCIAL PARTNERS

There are a number of ways in which commercial factors can play on moderation decisions..

There is the obvious threat of withdrawal of revenue sources like advertising that we have seen used on a number of occasions against large platforms.

This sometimes takes the form of individual company advertising boycotts but we have also seen more structured groups develop with the explicit aim of using advertiser power to influence platform policies.

There are also more indirect points of pressure such as the withdrawal of services like payments and essential security tools in response to concerns about the content being hosted by their customers.

This effect has been seen in decisions by PayPal and Cloudflare that put these non-content businesses in a position of acting as major influences over the viability of some websites.

POLITICAL PRESSURE

Where a service has established itself as a business and is looking to have a viable future then it is going to be sensitive to the views of relevant politicians.

These views may be expressed both overtly as political leaders publicly challenge companies over their perceived failure or covertly as they make private requests directly to services to take a particular action.

The overt pressure may take the form of regulatory proposals that will use the force of law to bring platforms into line, or may be of a ‘name and shame’ variety where companies are called into summits, committee hearings etc.

Political pressure is often targeted at moderation by platforms but may also seek to persuade citizens to change their auto and community moderation practices.

For example, the UK government wants to reduce the prevalence of hate speech directed towards sportspeople by both challenging platforms to remove more of this content and threatening posters with more sanctions.

CONCLUSIONS

No model for content moderation will make everyone happy all of the time – there will always be those who believe there is too much intervention and those who believe there is not enough.

A realistic goal is to ensure there is more understanding of the equities that are being weighed against each other in making moderation decisions.

To do this we should look at all of the parties involved in decision-making from individual users through the platforms to governments.

And we should look at the range of factors that are likely to be influential as moderation policies and practices are developed over time.

Some of the new legislative models are likely to have a profound effect in that they will make platforms explain and defend their approach to content moderation to a powerful third party, a government regulator.

This will not necessarily make the decisions any easier as they inevitably involve trade-offs between the interests of content owners and those who object to the content being available.

But we can at least expect to be entering into a new era of insights into the decisions as material will be collected and published by regulators.

And we should get a clearer idea of what governments think good content moderation looks like through the guidance that regulators will have to produce explaining what they think platforms need to do to be compliant.

Content moderation – it’s a dirty job but someone has to do it.

Excellent. There are also ‘influencers” who are enmeshed in content regulation, like trade groups, lobbyists, etc. I mention this b/c it is these groups that will stop reasonable efforts at bi-partisan, effective solutions to the wild, wild west of social media.