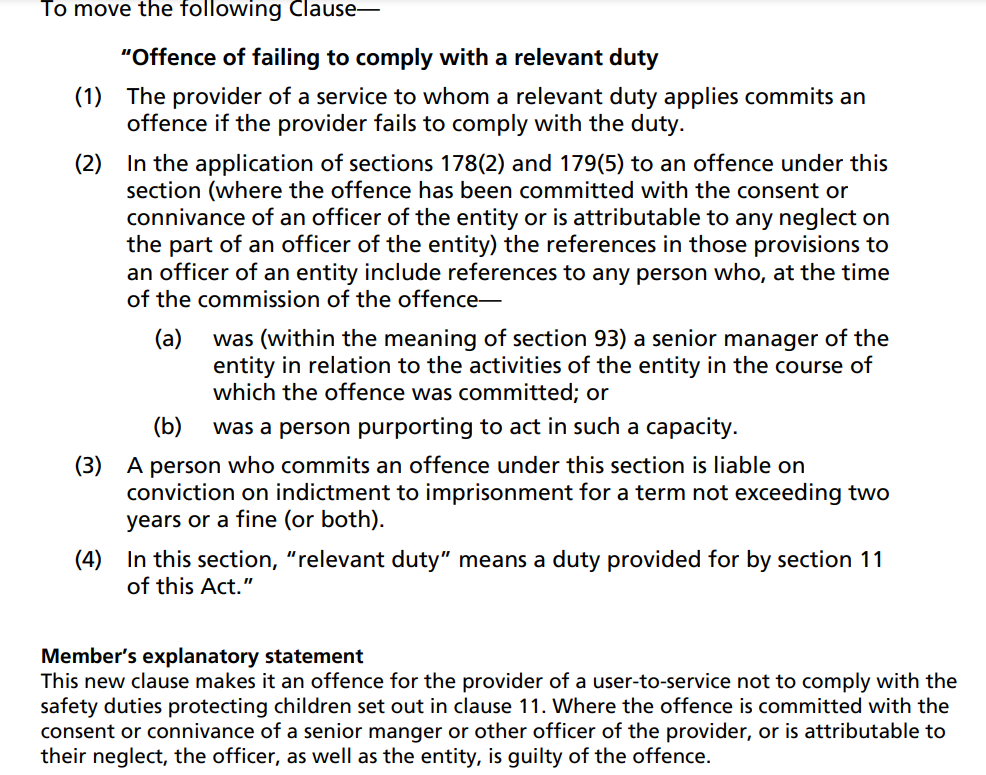

A group of MPs has tabled an amendment to the Online Safety Bill calling for tech company executives to be liable for prosecution in relation to failures by their services to meet new child safety standards that are created by the Bill.

It is understandable why such a move would attract political support given the levels of concern about harms that have been linked to the use of online services.

The logic of supporters of this amendment is that it will help to focus the minds of company leaders if they feel they may be held personally liable for any failings by their platforms.

But the risk of accepting this change is that it could serve to undermine the process that is the core mechanism through which the Bill aims to improve online safety.

I want to unpack why this would be the case and describe an alternative, and I think better, approach in this post.

An Engine For Change

Online platforms (at least the more responsible ones) have many highly skilled staff evaluating risks to their users and putting in place policies and processes to mitigate these.

They carry out risk assessments and test different models all of the time to see which approaches can best ensure bad content is removed while protecting good content.

The problem for governments and the public is that this work is largely done in private and we feel powerless in influencing how platforms define ‘bad’ vs ‘good’ content and shaping the tools they use to remove or promote it.

The Online Safety Bill aims to remedy this situation by requiring platforms to share their risk assessments with a regulator, Ofcom, and to explain what they are doing to meet various ‘duties of care’ towards their users in the UK.

I have argued and continue to believe that this will be a step change in terms of internet safety as the fact that platforms have to explain and justify their approach to an informed external regulator who could sanction them will have a significant positive effect.

But for this process to be truly effective, we need companies to be fully open and transparent with the regulator, sharing not just the things they feel they have well under control but also those where they are less sure of themselves and faced with difficult choices.

For example, a platform may have determined that there are significant risks associated with the distribution of content encouraging self-harm to children on their service and feel that they need an automated system to find and remove this quickly.

But they know that the automated system will also remove a certain amount of ‘good’ content items including news articles and advice pieces from self-help groups where these contain keywords or images that mean they are caught by the automated filter.

The platform now faces a tension between two of its duties of care – preventing harmful content reaching children and protecting legitimate content especially when this comes from the news media or someone who defines themselves as a journalist.

A key benefit of the new regime will be realised if the platform brings this issue to Ofcom with data showing the effects of more and less aggressive implementations of their self-harm filtering tools ,

This would create the conditions for a healthy discussion about where the balance should be struck and Ofcom will have guidance and codes of practice available to help direct platforms to the right place.

Ofcom may ask the platform to test different versions of their filter and report back for a further evaluation, or Ofcom may suggest new approaches that it has seen other platforms use to assess whether these would be appropriate and helpful.

Improving internet safety like this is an iterative process where different solutions are tested and then implemented when proven to be effective, and in most cases it will mean applying a balancing test between duties in respect of safety and of freedom of expression.

Where Ofcom feels that a platform is not taking a risk seriously or that their proposed solutions are not going to work then they can issue an order requiring a platform to take specific measures that will bring them up to the duty of care standard.

So how does the criminal liability in the proposed amendment affect this process?

First, it will have a chilling effect on the way in which platforms engage with Ofcom as they work through the process of assessing risk and explaining their mitigation measures.

Rather than being open about any areas of weakness, which is precisely where openness is important, there will be a strong incentive for platforms simply to say they believe they are already compliant with all of their duties of care.

They may move from an open, collaborative approach to their engagement with the regulator to a defensive one where they seek to meet their legal obligations while giving away as little information as possible that could later be used against them.

It would also affect which individuals from a company are willing to engage in the regulatory process.

The best outcome is for the senior leaders who run a company’s safety operations to be happy to work directly with the regulator explaining why they have made certain decisions and being open to challenge from the regulator on these.

For example, if we are talking about filtering out self-harm content we would ideally want the Director of Safety who owns the relevant algorithm to explain why they have designed it in a particular way and for Ofcom to test and contest their decisions if they feel this is necessary.

Under the current framework in the BIll I think there is a good chance of this happening with companies feeling able to share information with Ofcom as they explore exactly what a duty of care means.

One of the things I was most pleased to achieve at Facebook was to enable exactly some of these conversations between senior safety people and government officials as I think they benefited both sides.

But the company people would always be concerned about legal risk and I had to reassure them that this was manageable and worth it and in most cases colleagues accepted my assurances and the conversations could happen.

If the amendment passes in its current form then the risk assessment will clearly change.

If the Director of Safety steps forward as owning the decision about the algorithm then company lawyers will advise them that this exposes them to personal risk, and they will instinctively be much more hesitant about being involved in any meetings in the UK.

The company will also not want to admit to any uncertainty about the right solution in case this is later judged as a failure to meet their duty of care – an outcome that is quite likely as we are still working out exactly what the right standards should be.

So rather than having the real owner of a tool coming forward explaining the challenges and trade-offs, and describing various options that they think might work, you will get a regulatory lawyer coming to Ofcom to explain how everything they are doing absolutely does meet the duty of care and being careful not to admit any doubts or weaknesses.

This is not the companies being awkward but simply a rational and inevitable response to a new legal risk.

Courts vs Regulator

We also need to consider how prosecutions might work in practice under the proposed model.

Prosecuting someone for their ‘consent’ or connivance’ in a failure to meet their duty of care would require two tests to be satisfied, first that the platform did not comply with the duty, and second that the officer consented or connived in that non-compliance.

This first test would necessarily mean the court having to take a view on what compliance with the duty of care set out in clause 11 actually means but this is no simple task given the deliberately non-specific language in the Bill which talks about ‘proportionate measures’ rather than giving a list of yes/no requirements.

In the example I used above of various options for algorithms to remove self-harm content we are looking at a process of trying to find the sweet spot where the service meets both its duty to protect children and its duty to protect legal speech knowing that it can not be perfect in either dimension.

Ofcom has the capacity and a process for working with platforms to try to get to that optimal place but the courts do not.

The courts might just decide that they do not want to make any determinations on matters being considered by Ofcom in which case the prosecution process would not add anything material and risks leave complainants frustrated at a lack of prosecutions.

Or prosecutors could decide to take on the cases resulting in the courts creating their own definitions for compliance with the duty of care which may end up differing from Ofcom’s assessment within the broader regulatory process.

Continuing with my earlier example, Ofcom might decide that an algorithm which removes 90% of self-harm content at the cost of the occasional erroneous removal of legitimate content is reasonable while the courts feel that the duty of care is only met if a platform can show it is removing 98% of these content items even if this means more legitimate content removal.

This would not be a great outcome in terms of regulatory certainty and legal predictability.

If Not This Then What?

The Bill already creates a threat of personal liability for company officers who refuse to provide information or give false information to Ofcom.

This is sensible as the whole process of engagement around improving safety depends on services giving Ofcom the information they need to assess whether platforms are compliant.

There is also a process in the Bill for Ofcom to issue various kinds of directions to platforms where they are not satisfied with the measures that they are putting in place.

In many cases there will be agreement about what needs to be done but where a disagreement remains then Ofcom has powers to override the views of the platform.

A reasonable approach to ensuring company officers feel personally responsible would be to ensure they can be sanctioned if they deliberately and knowingly fail to implement Ofcom directions.

This could be done by including extra sanctions in Clauses 126 and 127 which govern the penalties that can be imposed for failures to follow confirmation decisions and notices.

An advantage of this approach is that it would be much more straightforward to prosecute.

The courts would have a written direction from Ofcom in front of them and can test factually whether or not the company complied with it and they can establish who received the direction at the company and took the decision not to comply with it.

There would be no need for the court to come to its own view of what constitutes compliance with the duty of care but they would rather start from the point that Ofcom has done this assessment and only issued a direction because there was a failure.

Looking Ahead

The Online Safety Bill is long and complicated and only looks like getting more so as it passes through Parliament where there is a tendency for Bills to grow by accretion.

This Bill is peculiar in that it has both grown and shrunk during its passage as the Government removed some of their original measures.

It is going to keep many people busy for years as not only the primary legislation but many pieces of secondary regulation have to be drafted and scrutinised.

I will keep taking part both because it is fascinating from a law-making point of view but also because I am invested in making it as workable and effective as possible.

I hope that any posts here will be accepted in that spirit and help inform the debate even where you disagree with what I have said.