Some years ago, I met with a senior official at Turkey’s internet regulator who said something that stuck with me :-

“You know, Richard, we would have no problems with Facebook if you could just keep the politics off your platform. All the family photos and games are great, but when people start using your service for politics then we have to get involved. You could have a much easier life without the politics.”

Comments by official at Turkish telecoms regulator (paraphrased).

[NB while there was always a hint of coercion in this kind of conversation with regulators, the official here was genuinely puzzled as to why we would want the trouble of being in the political business outside of any concerns his government had].

Fast forward a few years, and we see businesses deciding to suspend advertising on social media platforms in light of the political climate in the US :-

“We have made substantial progress, and we acknowledge the efforts of our partners, but there is much more to be done, especially in the areas of divisiveness and hate speech during this polarized election period in the U.S.

The complexities of the current cultural landscape have placed a renewed responsibility on brands to learn, respond and act to drive a trusted and safe digital ecosystem.

Given our Responsibility Framework and the polarized atmosphere in the U.S., we have decided that starting now through at least the end of the year, we will not run brand advertising in social media newsfeed platforms Facebook, Instagram and Twitter in the U.S.”

Unilever statement, June 26th 2020.

While the underlying motivations are quite different in each case, the common conclusion for social media platforms is that life would be a lot easier if they were somehow ‘less political’.

There are of course a host of counter-arguments as to why it is important for online platforms to provide as open spaces for political expression as possible.

But, in this post, I want to consider how platforms might evolve if they continue to find that political content is causing harm to their businesses.

This will be framed in terms of ‘business logic’ which I do not see as being entirely about money and free of any other values.

Of course, financial factors are supremely important for businesses, but their success depends on ‘reading society’ so they can provide products that people want over the long-term and adapt their products as consumer demands change.

Companies can take quite different stances in terms of being more conservative, ie protecting their existing products by resisting change, or more progressive, ie placing themselves at the forefront of change to try and capture the future market.

What they cannot do, if they want to stay in business, is shift their products dramatically away from anything that their customers might actually want today or tomorrow.

Special Election or Steady State?

It is possible that the current turmoil reflects a particularly divisive candidate and set of issues in a particular election in the US.

This might then subside once that election is over (assuming the divisive candidate loses) and ‘normal political service is resumed’.

The fact that US elections involve so much money and are fought so robustly certainly does make them unusual when compared with elections in many other countries.

But they can also set the trend for what happens in other countries as tactics are developed in the US and then exported to other countries by political consultants.

(This phenomenon of shared tactics is especially seen between political operations in the ‘Five Eyes’ countries so consultancies from the UK and Canada might work for US campaigns, or those from Australia and New Zealand play a key role in UK elections).

The political class in every country also follows US political developments closely and will often take up the same concerns, as we have seen recently with the global response to the Black Lives Matters movement, so what happens in US campaigns has an outsize influence.

We should also be careful when seeing polarisation as a new or transitory phenomenon that we are not looking at the past through rose-tinted spectacles and ignoring a reality of heated political contests being more the norm than the exception.

If we look at the well-documented use of hate speech in UK election contests of the 1960’s, it is not necessarily the case that more people are using hateful language today but that, with social media, hateful political speech has become much more visible and is able to circulate more widely.

All of these factors point to the toxicity of election campaigns becoming an enduring issue for platforms as political debates increasingly play out over social media around the world.

Adaptation Options

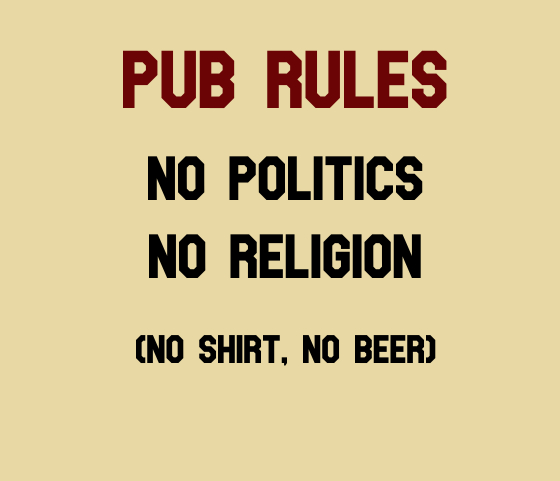

This is where the ‘pub rules’ of the post title come in.

What came to mind as I considered this notion of heated political debate being toxic is the old adage that you don’t ‘talk religion or politics’ in the pub.

The logic behind that saying was that arguments over these issues could similarly pollute what is a pleasant social space.

In my fairly extensive research into pubs and politics (a necessary part of being a candidate I am sure you will understand), I have found that there are in fact various models that can be used as analogies for platform approaches here.

As well as the ‘No Politics Pub, we can look at the ‘Polite Politics Pub’ and the ‘Partisan Pub’.

No Politics Pub

It seems unlikely that any of the major global social media platforms could ever become truly ‘politics free’ even if there was a business logic propelling it firmly in that direction.

This was part of my response to the Turkish regulator I cited at the start of this post – if people in Turkey wanted to talk about politics there was no way we could stop that even if we agreed with it conceptually (which we did not).

There are examples of social media platforms, such as Sina Weibo, that do suppress a great deal of political content but it is hard to imagine these models being accepted where there is no state compulsion to do so.

But there are moves that platforms could make, short of a full censorship model, that would still make them much less political.

Platforms usually offer special treatment for key individuals and organisations that they want using their service and have considerable discretion over what should be offered to whom.

They might permit political content producers to sign up but not help them to gain traction in the same way as influencers from sectors they do favour, like music, fashion and entertainment.

Where content consumption is based on recommendation engines, then ranking political content lower than entertainment content (or excluding it altogether) would also give a service a much less political ‘feel’ for most users.

[NB in case you think I have gone ‘full autocrat’ here, a reminder that I am exploring where external pressures may push platforms not describing what I personally think would be good outcomes].

Polite Politics Pub

People do of course often talk politics in pubs, but they generally do so politely in ways that do not disturb other people.

If platforms could enforce a model of polite discourse, then this would meet the demand from advertisers whose concerns relate to nasty speech rather than all political speech.

In my pub analogy, the problem is not with the reasonable conversations, but with the loud group of skinheads at one table who are using profanities and racist language, and creating an atmosphere of imminent violence.

[NB I know that not all skinheads were far-right supporters but the ones who I had to avoid as a teenage punk were I think sadly typical].

In this model, platforms would still allow and even encourage political content, but insist that it stays within boundaries that exclude the extremes.

In practical terms, they might adjust their stance on violent language so that it prohibits a broader range of threats, not just ones that are credible.

They might limit other forms of aggressive language in political discourse, such as strong curse-words.

This would certainly not be a ‘First Amendment’ position and many people may feel constrained if they cannot curse and threaten politicians at will, but it is a stance that platforms could defend and may find is popular with a majority of their users.

The UK Parliament has been asking for such an approach for some time as they believe that strong language and threats on social media are harming democracy.

There is a risk that prohibiting ‘stronger’ political speech would have partisan effects, even if that is not the intent, as I talked about in relation to hate speech rules in an earlier post.

I will use an example from Germany as this is something that a very thoughtful journalist raised with me when we were discussing hate speech in Berlin.

We can imagine two ways in which voters hostile to the current German Chancellor might have expressed themselves in the last election :-

A. “Angela Merkel is a terrible leader - she let in thousands of foreigners and the country can’t cope - we should throw her out”; B. “That b***h Merkel flooded the country with Muslims - she needs to f**k off”.

In the ‘polite’ speech model, A would be unexceptional, while B would be unacceptable.

The effect of policy changes might not be a simple one of a left-right bias (much of the strongest speech today is against the US President) but they would likely impact more on those who use more ‘vernacular’ speech.

A shift to more ‘polite’ speech may be seen as necessary and desirable, but we should recognise any differential impact on groups in society and consider the political impact of this.

If this is felt to impact more on some political factions than others, however unintentionally, then people may experience this as the platform moving not into a ‘polite pub’ mode but into my third model, the ‘partisan pub’.

Partisan Pub

If it is the heated nature of the political debate that is causing toxicity, then one way to take the heat out is to have only one side of the debate present on a platform.

I used to frequent a pub in South London called The Bread and Roses that was run (very well IMO) by the ‘Workers Beer Company’.

The pub was overtly ‘of the left’ and would host political groups and meetings without any tension as everyone knew what to expect.

On the other side, the UK has many ‘Conservative Clubs’, some of these are now apolitical, but many retain close ties to local right-wing politics.

This is also the model we see in classic media where newspapers (at least in the UK) operate within communities of largely like-minded people.

People from the ‘other side’ may come over to troll you from time to time but the core content and activity of a newspaper website nicely aligns with the politics of the people who choose to visit it.

Social media platforms have to date not tended to align themselves with one political angle as an explicit policy even if they are often accused of doing so.

There has been a compelling business logic for platforms not to alienate large groups of actual and potential users by being pigeon-holed as being only for people of one political persuasion.

But, there are two forces that are shifting the business logic so platforms may now have to consider a future in which they accept that they have a partisan identity.

First, we are seeing some user interest in creating their own politically aligned spaces.

This has largely been associated with the far right and reactive to people being banned, and it is not yet clear how far this will spread to the broader user population but there are signs of more mainstream influencers getting in on the act.

A current trend is for (right wing) influencers to announce that they have signed up to a service called Parler as a response to perceived bias by Twitter.

This has not yet translated into a significant forking of user bases but this could accelerate if Twitter takes more actions that people on the political right feel are biased against them.

We see something of the reverse phenomenon in respect of Facebook where people on the left cite a lack of action against the political right as cause for them to look for alternative social media homes.

So we have this external force of people seeing platforms as either favouring the left or right while the platforms themselves assert their continued neutrality.

This might lead platforms to a ‘go-with-the-flow’ position where they see their business interests as better served by accepting rather than fighting their perceived position on the political spectrum.

Second, there is a sense that some of the political questions currently up for debate are so profound that business neutrality is no longer an option.

This is sometimes expressed as businesses needing to take an ethical decision about whether they want to ‘be on the right (or wrong) side of history’.

I am sure many businesses taking a stand have strong ethical motivations and are people of integrity, but they will also need to take a view on whether this puts them on the ‘right side of evolving consumer sentiment’.

I do not say this in a spirit of cynicism and these are not either/or motivations – you can be both committed to something ethically and see it as having a sound business logic.

This is in fact the ideal position to be in as a business leader, where the analysis tells you that your company’s interests are aligned with advancing an agenda that you care about.

Conversely, business leaders are in a bad place if they feel there is a significant gap between the ‘right’ position to take and the interests of their company.

The pressure is now on platforms for them to become more partisan – creating a more hostile environment for the far right and bigots, while welcoming campaigners fighting these forces.

If a platform believes that society is strongly moving in that direction, then there is a business logic to their accepting this pressure and aligning with where people are going to be not where they used to be.

In crude terms, a platform may decide it is worth losing some users now in order to gain more users later.

But this is not without ethical issues of its own as it puts platforms squarely into a place of exercising more overt influence over politics and elections.

Whither Platforms?

Each major online platform offers its own particular value proposition to their various target audiences.

There will be a different business logic for each of them in responding to pressures over political content.

If users are coming to a service for political content then it would not make sense for them to move to a ‘no politics’ model, so it is unlikely that ‘chatty’ services like Twitter and Facebook would or could become politics-free.

But for services that are focused on delivering engaging visual media to users, like TikTok and Snapchat, there may be a business logic to reducing the visibility of political content if this is hurting the platform.

This would not necessarily involve removing political content, but political content may become less discoverable, and there may be strong cultural pressures making a service less welcoming for some or all political actors.

Instagram did not actively welcome political influencers in its early days as being somewhat counter to the creative culture it wanted to create, and might be attracted to reducing the prominence of political content.

Instagram may be especially interested in the ‘Polite Politics’ model as this would be consistent with the approach it has been developing towards bullying and harsh comments more generally.

If a service has already decided to reduce the visibility of content that uses strong curse words and aggressive language then this will mean that harsh political language is also less visible.

It is helpful to consider Facebook and Twitter together and whether they will become more Polite or Partisan (assuming they will keep moving under pressure).

There is already a sense that Twitter is becoming Partisan, whether it likes it or not, after a number of high profile interventions that have been interpreted as hostile by the incumbent US President.

There does now seem to be some kind of prospect of ‘Right flight’ from Twitter to other platforms (though there have of course been false starts before and this could peter out).

The question for Twitter is the extent to which this would harm them, ie what is the business logic for them to resist such a trend.

No platform wants to lose users, but this is not necessarily an existential threat for Twitter given the way in which it provides value to people.

Twitter does not pretend to replicate offline social environments online, but rather provides a massive array of communities of interest for people to join.

People derive significant value from regular, topical updates from the sources they follow and communities they engage with on the platform.

If a subset of sources and communities were to migrate to another platform because they felt Twitter had become hostile to them then this does not necessarily diminish the experience for other people not in those groups.

There might even be an increase in loyalty and engagement from those who have stuck with the platform that would compensate for the lost business.

The situation for Facebook is quite different in that its core value proposition is that it allows you communicate with all (or at least a significant group of) your family and friends.

While we do have political biases in our social circles, they usually include people with a wide variety of views including some that we may find objectionable but tolerate because someone is related to us.

If people were to start using different platforms for their Facebook functionality then this would create a diminished experience across all services as none could offer the ‘all family and friends’ experience.

This suggests that there is a much stronger business logic against Facebook allowing itself either explicitly or implicitly to drive out large swathes of people over their political views.

There is certainly scope for Facebook to push out people at the extremes but not to allow this to create huge gaps in social circles.

Twitter might, for example, be able to take a partisan stance that drives out the 25% of the population on the political right without this affecting its core value proposition to the other 75%.

But for Facebook, having a quarter of your family and friends absent for political reasons is a much more significant change to the product.

Family and friends networks are equally diminished if the absentees are from the left or right, hence the tight-rope walking that Facebook has to do so as not to alienate too many people on either side.

The business logic is then for Facebook to pursue a more aggressive Polite Politics model but to continue to be wary of being seen as overly Partisan.

This will be hard to execute, especially in a climate where every move is scrutinised and where any new content rules may create inadvertent partisan effects.

Twitter on the other hand may feel more relaxed about moves that cause others to characterise them as Partisan, and might even embrace this at some point as in their business interests.

It’s Personal

Before closing this post, I want to reflect for a moment on the particular nature of content-related toxicity as it applies to social media platforms.

I have found that people feel a strong sense of personal ownership of the social media platforms they use.

We are putting ourselves out there and this is reflected in the language we use, asking people to look at “my” Facebook profile, “my” Twitter feed etc.

This is a real strength as long as people love the platforms they are using but it can turn into a significant threat when people feel disappointed by them.

You can reject other brands and products if you are upset with them and move to substitutes, but with social media this means rejecting something that you have built and that you feel is part of yourself.

When we are angry at platforms, this reflects sincere personal feelings of disappointment that “our” service has become polluted by content that we find unacceptable.

Our anger is compounded by the fact that we have derived much value and enjoyment from a platform in the past, and we hate to see this taken away from us by what we believe are mistakes by those who run the service.

From a platform perspective, even if they agree with us over what constitutes “polluting” content, meeting our expectations can feel like an impossible task.

The nature of user-generated content platforms is such that post-moderation rather than pre-moderation is the name of the game, and I have written more about this previously,

This means that ‘bad’ content is likely to exist on platforms for a time even where it does breach the rules and is later removed.

And this need to post-moderate is not just an issue for large platform with masses of content, but may be even more acute for smaller platforms which have fewer resources and may take longer to remove bad content.

Larger platforms do have a particular problem with errors – both leaving up bad content that should come down, and removing good content that should have stayed up.

Even with very low error rates, operations working at massive scale will make significant numbers of errors, for example a 1% error rate on a million moderation decisions means 10,000 wrong decisions.

If you look for them, you will be able to find examples of both under and over enforcement every single day, and it takes just a few examples to confirm any views that people already have about the values or biases of platforms.

So, this is going to be hard, whichever stance platforms take, unless they can achieve perfect enforcement which seems unlikely in the near future.

But there is a hunger to understand from platforms whether they are committed to a particular direction of travel and an urgency for them to spell this out.

Summary :- I look at the ways in which online platforms might respond to pressures related to toxic political content. I consider variations of rules for discussing politics in pubs. I describe the business logic that may apply to specific platforms.