If you live in the UK you will likely have been amused by a video produced by the comedian Matt Lucas sending up the Government’s advice on what people need to do in response to Covid-19.

The phrase ‘go to work, don’t go to work’ has become a zeitgeist response whenever we think that official communications are less than clear.

This also feels like a good description of the messages that internet services receive about whether they should be using automated tools to detect and remove ‘bad’ content.

Go To Work

Policy makers often express a desire for platforms to use more scanning of content to keep their services (and society) safe, and have created legislation that many people interpret as effectively mandating the use of this technology.

Legislation may not make an explicit direction, but it is understood that policy makers mean for platforms to use scanning when they include terms likes making ‘best efforts’ (EU Copyright Directive) and ‘proactive measures’ (proposed EU terrorist content regulation).

Independently of this being required by law, user-generated content platforms have developed the use of scanning tools over the years as a way of mitigating the risks they face when allowing people to upload content to their services.

There is a strong business case for platforms to build systems to identify illegally shared copyrighted material as they would otherwise face endless lawsuits from rights owners and/or have to make it much more difficult for users to share content over their services.

Most major platforms also scan for child sexual exploitation material by comparing uploaded images and videos with a database of known illegal content and removing any new instances immediately.

This use of scanning for child protection was developed early both because of the appalling nature of the crime and because legal regimes mean that platforms have to take particular care about how they handle this kind of material.

Notably, there is a specific legal requirement for US providers to file reports about the illegal child sexual exploitation material they find with an organisation called the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC).

These image and video matching techniques can also be useful for preventing the distribution of other types of images and videos where there is a set of known examples that are being repeatedly shared.

Typical cases where the same technology may be used today are in preventing the spread of non-consensual sexual imagery of adults (often referred to as ‘revenge porn’) and terrorist propaganda.

As well as scanning for known images and videos, platforms may have tools that look for certain types of behaviour and language that people are using.

As far back as 2010, Facebook was under a lot of pressure from the UK government and child safety agencies to identify sexual predators using social media to find new victims through a process known as ‘grooming’.

This predatory behaviour can be a problem in any space where people come together and social media was no exception as we have seen from many horrific cases over the years.

These conversations are unlikely to be reported to a platform as long as the victim remains under the sway of the abuser so the question was naturally raised as to whether the platform could spot these situations through its own investigative efforts.

The precise ways in which safety teams do their work changes often in response to threats and requires a certain level of secrecy, but you can imagine the kind of indicators that might be useful here to identify an older user who is sending sexually explicit messages to younger users over private channels.

As with scanning for specific content, if a child safety need was an early use of these techniques, which look at connections and message content, then there are other situations where they may also be useful such as in identifying people at risk of harming themselves or attacking others.

Policy makers in the UK called for more use of these systems to identify potential terrorists after the murder of Fusilier Lee Rigby in 2014.

More recently, there has been significant interest in a number of countries in the way in which platforms manage hate speech as this is seen to be a contributor to social conflict.

The huge variability in the ways people can use written language makes for a different challenge from that of identifying bad images and videos, but advances in natural language processing techniques over recent years are giving platforms confidence they can also accurately identify bad text.

You can see how these text detection methods are being used by Facebook in their August 2020 Community Standards Enforcement Report which says that 95% of their hate speech removals are now of content that was flagged up by their automated scanning tools.

This may sound like it is all in the ‘go to work’ camp, and that policy makers must be universally happy that platforms are now using scanning in many of the areas where they asked for more to be done, but a remarkable (and largely unremarked) debate is happening in the European Parliament that presents a more complex picture

Don’t Go to Work

The discussion in the European Parliament is looking at the tools that I described as being voluntarily adopted early on by platforms – scanning for child sexual exploitation material and identifying sexual predators grooming child victims.

The debate is about the legality of using these tools, at least in the context of EU users of messaging services, and raises arguments that are also relevant for the raft of other tools that have been developed more recently.

If you want to look into the detail of the positions being taken then I would recommend reading the blog of longstanding child safety expert John Carr who has been chronicling these developments.

There was a risk that one piece of EU law, concerned with the privacy of communications, was going to make scanning illegal, with this consequence only really being identified very late in the day.

A political fix has been proposed that is intended to provide legal cover to platforms so that they can continue to scan for these specific purposes as long as they meet certain conditions.

The immediate cessation of these tools may have been averted, but the debate has flagged up a range of policy concerns about scanning for harmful content that will be important for the broader platform regulation debate.

As an example of how this kind of policy uncertainty has effects, Instagram has described concerns about EU legal compliance as causing it to roll-out tools that scan for suicidal and self-harm content more slowly in the EU than in the US.

To Scan or Not To Scan, that is a Duty of Care Question

This is an area where there are real trade-offs to be made – scanning content, especially private messages, is a form of observation, but it can also bring significant demonstrable benefits in terms of harm reduction.

This week also saw the publication of plans by the EU and the UK to legislate with the goal of making digital services safer by placing them under new obligations and oversight.

The language being used to describe this new framework, especially in the UK, is that platforms should see themselves as having a ‘duty of care’ to people in countries where they operate.

This gives us a useful way to consider these questions about the use of scanning technology – do we think platforms are meeting their duty of care by deploying particular tools, or refraining from doing so?

The answer to this is not going to be a simple yes/no but will rather depend on an analysis of a particular harm, the effectiveness of the specific form of scanning that is being used to address it, and any privacy or other risks that the scanning might create.

It is not helpful to look at this generically as “scanning good” or “scanning bad” but rather to consider each specific deployment decision on its own merits.

[NB ‘slippery slope’ arguments are not persuasive in this area – we can perfectly well require platforms to scan for some things while prohibiting them from scanning for others if that is what regulators want to happen.]

This kind of detailed dialog about particular harm reduction strategies will hopefully be a major part of the engagement that platforms have with UK and EU regulators under the new regimes.

For example, we might imagine a discussion on the use of grooming tools where platforms describe to the regulator the indicators they use, how many people this flags up for review, what proportion of the reviews lead to actions being taken, and the controls they have in place to prevent abuse.

Where the details of the process show that tools are targeted accurately and preventing serious harm from occurring then the regulator will judge that this form of scanning is consistent with the platform’s duty of care.

For a different harm like hate speech, the regulator might take the view that scanning should be limited to spaces where content is shared publicly, and that it is not appropriate to scan private messages in this instance.

The important shift is that there will be a dialogue between platforms and regulators where all of the interests can be balanced up and an authoritative view taken on what the right approach is for a ‘careful’ platform.

This is better for public accountability but also for the platforms than a status quo in which they may be hearing ‘scan for bad stuff’ or ‘don’t scan for bad stuff’ depending on who they talk to in government.

Postscript

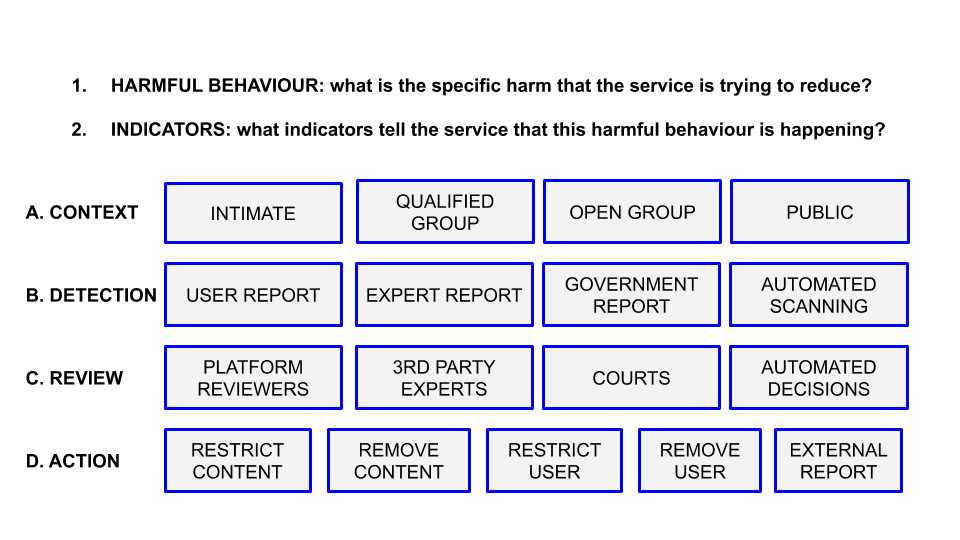

I will come back to the idea that we might structure the work that regulators do with platforms around ‘harm reduction plans’ in another post, and offer the diagram below as a teaser for this.

Hi Richard,

Greetings from a former FB colleague from the LERT team in Dublin.

First time reading your blog’s post. Excellent reading and so timely. Thanks for bringing your thoughts and expertise to this important and so crucial discussion. Although I never worked closely with you I always admired your approach. Thanks once again. I’ll keep following you! I mean, your blog posts 🙂