I spent a happy couple of days last week reading hundreds of pages of the UK draft Online Safety Bill with its explanatory notes and impact assessment.

This legislative proposal is going to be scrutinised in detail over coming months as people try to flesh out what it will mean in practice before a final text makes its way through Parliament to become law around 2023.

I talked about the Bill with Nicklas Lundblad in last week’s episode of the regulate.tech podcast but thought it would also be useful to put some of this down in a post.

This is necessarily a non-exhaustive list as there is so much interesting stuff to be found in these substantial documents, but here are some initial thoughts about what it means for the internet sector.

- This is what a comprehensive regulatory framework for search and social media looks like and this means a lot of new legal definitions and provisions – 145 pages just to describe the new structure and legal powers for the regulator, with many hundred more pages to follow in secondary legislation, codes of practice, guidance etc.

- There is a requirement for services to produce ‘risk assessments’ that could form the basis of productive conversations between platforms and the regulator along the lines of the ‘harm reduction plans’ that I have described.

- The law would also allow the UK Government to micro-manage the internet sector if it were so minded, from defining who is in and out of scope (clause 3), through explicit direction from politicians on priorities for the regulator (clause 33), to the regulator directing companies to implement specific technical solutions to scan for some types of illegal content (clause 63).

- The law will create a series of new risks for tech company execs including criminal penalties if they refuse to provide information when requested or provide wrong information (clauses 72-73), and powers to demand they attend interviews even if based abroad (clause 76 and 127).

- It includes measures that would allow the UK government to order app stores not to carry services that have not complied with UK law (clause 93) and to order ‘ancillary services’ like advertisers and payment providers not to cooperate with them (clause 91).

- It sets up some interesting tensions as it is designed to put pressure on platforms to remove more ‘bad’ content, of both the illegal and ‘legal but harmful’ kinds, whilst also protecting freedom of expression, and these competing goals are not explicitly reconciled in the primary legislation.

- It calls for special treatment of journalistic content and news media providers and politically important content opening up questions about who can say they are a journalist or politician and demand their content be given special protection.

Those are some of the questions raised by the legislation, but it was the 146 pages of the Impact Assessment (IA) that I found immediately interesting for its insights into how this might actually work.

I have questions about some of the estimates in the IA but should say at the outset that I think IAs are a really good thing as they put the government’s assumptions into the public domain and allow us to test them against our own knowledge and experience.

Top of mind will be to understand how many internet services will be covered by the law and the IA provides an estimate that 24,000 entities will be in scope.

Most of the new costs will fall on these in scope entities but there will also be some costs for a broad range of internet services who will eventually be determined as out-of-scope but need to do work to establish this fact.

It is hard to judge how accurate this is but ‘thousands’ seems in the right zone given that the law excludes most websites that only post their own content, rather than offering ‘user-to-user’ features, as well as a range of other services.

The IA then predicts the new costs that the legislation will create for businesses and some of these numbers seem quite at variance from my experience working on related issues.

You can see them all for yourselves in the full 146 page document and may wish to send feedback which they invite in a series of questions summarised at the end of the document (there is an email address for you to contact the team at the top of page 1).

The IA estimates the costs of three different policy options (as well as a baseline status quo option) following the age-old practice of having a ‘softer’ and ‘harder’ option to wrap around the Government’s preferred option 2 which is reflected in the Draft Bill.

In these ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bears’ choices, the middle option is invariably the one that you are intended to feel is ‘just right’ (and, yes, I have written 3 option briefings just like this to present to leadership teams for decision).

I am going to focus on the Option 2 costs in this post as they are most relevant for the published Bill but the methods for calculating costs in the other options are also interesting if we want to think about alternative regulatory solutions.

To give a sense of scale, the IA estimates the costs of the Bill as being £2bn over 10 years, or roughly £200m per year (though they place some costs only in a transitional phase).

They estimate most of these new costs as coming from the need for additional content moderation which seems reasonable, but they also predict the costs for the more ‘bureaucratic’ changes that the law will require.

We can dig into the first three questions which were on the costs to services of 1) getting familiar with the regulation, 2) changing their reporting systems, and 3) updating terms of service.

Reading The Regulation

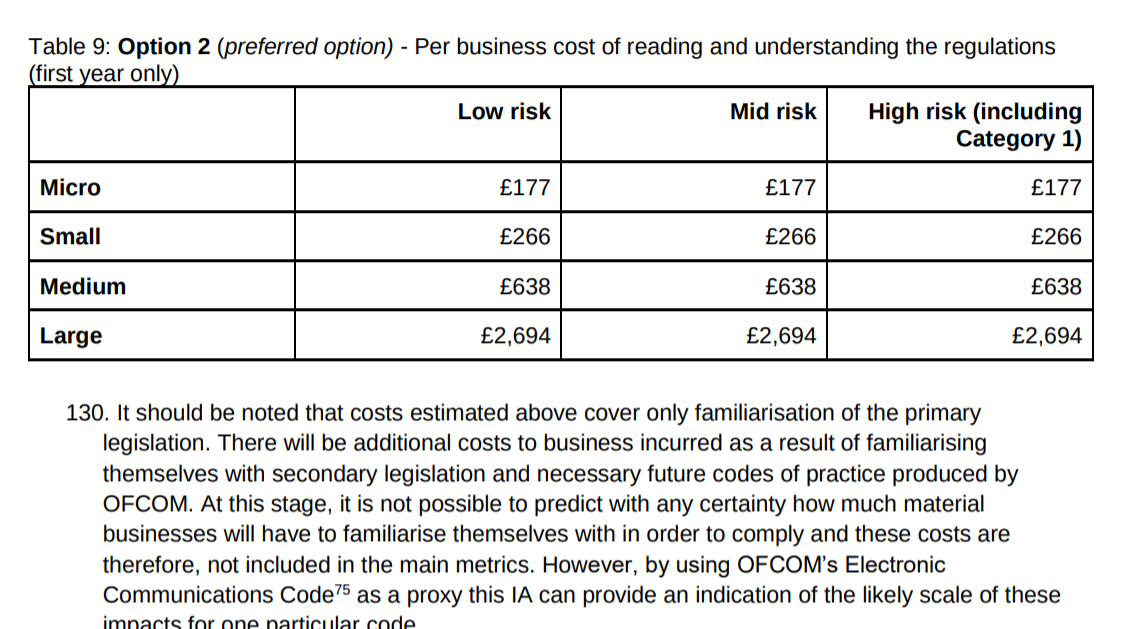

This first estimate just covers the cost of reading the primary legislation so would anyway need to be significantly increased to reflect the cost of understanding the hundreds of pages of secondary regulation and guidance that the law will spawn over time.

These sums based on this assumption :-

For the initial familiarisation, one regulatory professional at an hourly wage of £20.66 is expected to read the regulations within each business. The explanatory notes are expected to be between 25,000 and 75,000 words and would therefore take between 2-6 hours based on a reading speed of 200 words per minute.

Draft Online Safety Bill Impact Assessment p37

There are some additional sums assumed for larger businesses who find they are in scope based on assumptions about their needing to have 10% of their staff spend 30 mins in a staff meeting or reading about the new regulation.

These assumptions may hold at the micro end of the spectrum where very small businesses might feel a skim-read is enough for them to understand their exposure.

We will most likely see third party services being developed and offered to small businesses so they don’t have to do this assessment themselves and these may cost a few hundred pounds, more than the assumed £177 but not orders of magnitude more.

But when we come to larger businesses who may be exposed to considerable risk and will need to build significant compliance functions then these assumptions seem way short of the mark.

This will not be a matter of having a regulatory professional read the documents but they will rather create large cross-functional internal teams to go through the law in detail and assess its implications for them.

And they will want to commission external legal advice from relevant UK counsel which will not come it at £20.66 per hour.

We might see this as significant a development for people working on content issues in a company as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was for those working on personal data, and the GDPR experience shows us that getting an organisation up to speed on a major new law is not cheap.

More realistic costs for the whole package of understanding the primary legislation and all of its accompanying guidance, which may change from year to year, would put these figures at thousands of pounds for all but the smallest of companies, and potentially millions for the largest.

Changing Reporting Systems

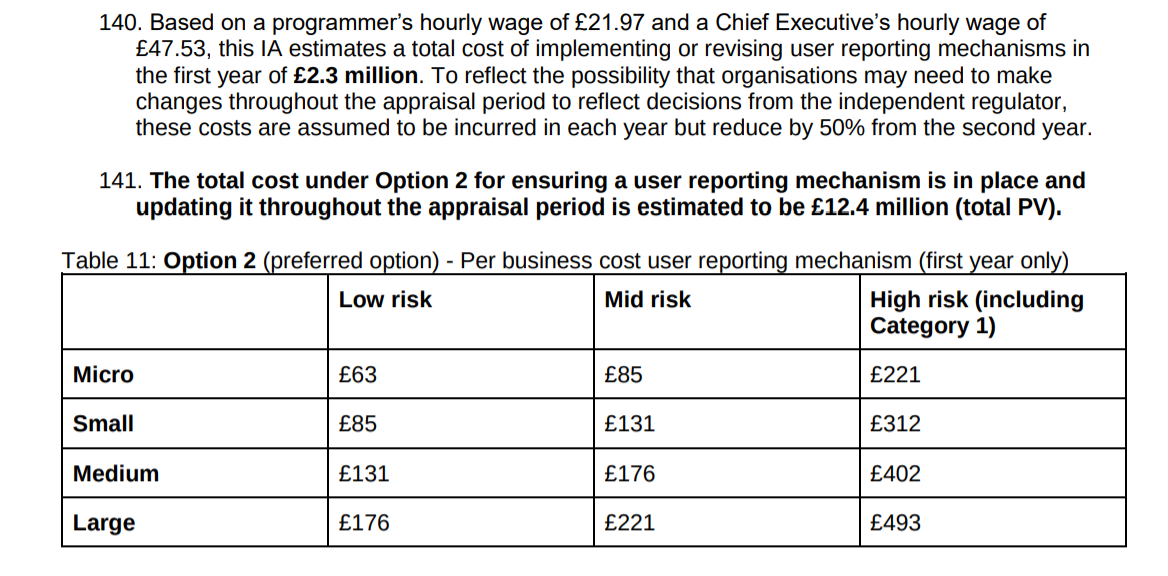

The law will place requirements on entities to offer people ways to report specific types of content or behaviour on their services.

The IA correctly notes that many services already have some kind of reporting system and then makes some assumptions about how much it would cost to update these to be compliant with the new requirements.

These costs are based on varying amounts of programmer time to code the changes plus an hour from the Chief Exec or a ‘Senior Official’ to sign them off.

The IA uses these assumptions :- ‘

While the costs will be considered further once the code of practice has been developed, to provide an indication of the likely scale of the impacts at primary this IA assumes varying degrees of programmer time to make changes to the internal reporting mechanism:

Draft Online Safety Bill Impact Assessment pp39-40

• Low risk platforms: 1 hours of programmer time for micro businesses (rising to 2, 4 and 6 for small, medium and large businesses respectively).

• Mid risk platforms: 2 hours of programmer time for micro businesses (rising to 4, 6 and 8 for small medium and large businesses respectively)

• High risk platforms: 8 hours of programmer time for micro businesses (rising to 12, 16 and 20 for small medium and large businesses respectively)

Again, these costs might be close to reality for micro businesses, who may simply put a new contact email address up on their website, but they feel way off for any entity larger than this which offers dedicated user reporting functionality.

When you are changing any kind of public facing feature on an internet service, especially a sensitive one like capturing reports of illegal or harmful content, then you are going to pull together a team to do this.

The team will have some ‘programmers’ to write the code but will also need a range of designers and content experts to assess different ways in which the form could be presented and how users react to various options.

And any change to an input form is likely to lead to more work changing the systems that process submissions through the form which sometimes means building entire new workflows for the content moderation teams.

The idea that a large company working in a high risk environment would only need to spend £493 on updating a reporting system that is needed for legal compliance is a dramatic underestimate – the true figure will run into many thousands when you look at such an update process in its entirety.

There is also an ongoing maintenance challenge as global services may update their reporting systems on a regular basis for all sorts of reasons and would have to ensure that the special UK features are not lost as they do this.

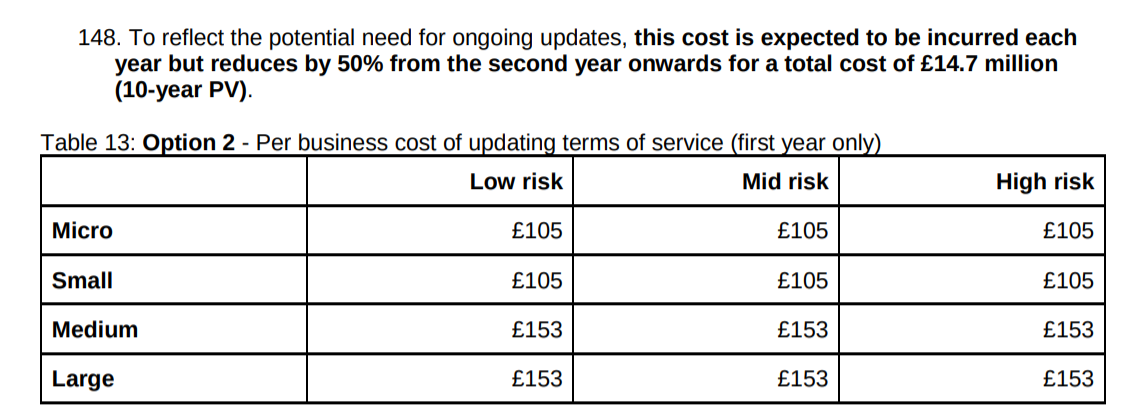

Updating Terms of Service

There are many elements of the Bill that require entities to make updates to their terms of service and the IA prices this work at between £105 and £153.

This may be seen as one of the positive aspects of the legislation – that it will make explicit in the contract between a service and its users a whole range of policies and practices that may be implicit at present and either not known to users or at least not actionable by them as they are internal policies.

Moving these commitments into the terms of service is a step change in terms of both user transparency and service accountability and precisely for that reason it will be seen as non-trivial by service providers.

Before any significant change to their terms most services will want to pull together a team to work through what the implications of any changes might be down the track.

This will likely be led by the internal legal team but they will consult with other people internally to understand how the new terms might impact their work and they may also want to engage external lawyers for advice on any new exposure to legal risks.

The figures for doing this work in the IA are minimal as they based on these assumptions –

For medium and large businesses (including Category 1 platforms), one regulatory professional at a wage of £20.66 is expected to read and assess the current terms of service and make the necessary changes. These businesses are likely to require an additional 2 hours of legal advice (assumed to be given here by a legal professional at a wage of £39.48). In addition, one hour of Chief Executive/Senior Official time for sign-off at a wage of £47.53 is incorporated. This IA therefore estimates a first year per business cost for medium and large businesses of £153.

Draft Online Safety Bill Impact Assessment p42

For a micro business that has essentially used boilerplate text for its terms of service the costs may in practice be quite low as we can expect some new “Online Safety Bill Compliant Terms” to come into circulation and they may feel it is low enough risk for them to cut and paste these into their old terms.

But for any larger business whose terms may be tested either by the regulator or in the courts then they will want to do this work very carefully and we are again talking about a cost of thousands not hundreds of pounds.

Not everyone will need the same scale of effort as a major player like Facebook (who have had repeated challenges landing their terms updates even with huge resources dedicated to this) but it is going to involve a lot more than one regulatory professional with a couple of hours of legal advice.

Finally, the Fees

One other question the IA answers is how much the fees on industry and likely to be, which also gives us a sense of how much the regulator, Ofcom, will expand to do this new work.

The IA tells us that –

DCMS has worked with OFCOM to estimate a reasonable and realistic ten-year profile of operating expenditure. This assessment estimates that the annual industry fee on average could equate to £46.0 million per year (PV) and total £346.7 million across the appraisal period (10 year PV)”

Draft Online Safety Bill Impact Assessment p60

To put this in context, OFCOM currently has around 900 staff and an operating budget of £125m.

There will be more complex calculations to make as the new online safety regulation unit is set up but we can see that the new system might increase the OFCOM budget by around a third.

If this is translated crudely into staff numbers then this would mean perhaps 300 more staff being taken on to do the new work.

Notably, this would be a bigger budget than is spent on regulating telecoms networks (£40m) and more than twice as much as they spend regulating commercial television (£12m) and the BBC (£10m) put together.

International Contagion

When regulations like this are proposed in countries that are generally regarded as respecting human rights and having good rule of law, like the UK, this often prompts concerns about how the same powers might be used by less benign governments.

We should explore these concerns with this legislation but we should be careful not to overstate the ‘slippery slope’ arguments in this context.

We should note that countries seeking more control over the internet have been moving on this for some time, for example the Russian Duma has enacted a number of laws that allow their regulator Roskomnadzor to place requirements on internet service providers.

Service providers are already having to decide the extent of their willingness to comply with regulatory controls and the new UK law does not materially change those calculations in other places as these are based on a country-by-country assessment of the human rights implications of compliance vs defiance in that place.

What the UK law will do is give some countries a new line of argument to defend their own regimes arguing that ‘even the UK is doing something similar, so we can’t be that bad’, but this is a political argument rather than a change in the fundamentals.

As we consider the contagion questions, we should also work through what will happen if a UK-like model is adopted in many countries where services would have no human rights grounds to refuse cooperation and their expectation would rather be full compliance with the associated costs.

If we fast forward a few years, we may see a situation where a new internet service that is offered globally will, once it starts to gain users in multiple countries, receive communications from dozens of regulators asking it to pay them fees and make specific changes to comply with the local regime.

Absent any human rights concerns that would rule out compliance, the question will then be whether the compliance costs are worth it for the value of having users in that country.

The EU might lower the compliance burden if it is able to adopt a ‘one stop shop’ regime where services are only regulated in one of the 27 member states but this may prove challenging given that attitudes to restrictions on content can vary widely between different EU countries.

Even if the EU is able to agree on a single regime, and assuming the US stays out of the game for First Amendment reasons, that may still leave a service with a long list of regulators asking for their time and money.

I do not expect the costs question to prompt an outpouring of sympathy for tech companies, and the rationale driving the UK law and debates in many other countries is precisely that of feeling the ‘time has come’ to bring internet services into a more closely regulated regime including paying their dues.

But as we open the doors to this major change in how internet services will be regulated, we should be clear-eyed about the potential impacts on costs and on how the global market will operate.

The Future

This is something to come back to as we consider legislation across multiple markets and not just the UK, but here is an initial hypothesis to ponder as we do that.

Micro businesses will be able to carry on largely as they are today, with some new costs that they will pay to ‘compliance consultants’ in each country where there fall into regulatory scope.

This compliance work will likely cost quite a lot more than the kind of optimist estimates we have seen in the UK Impact Assessment, especially in countries where the requirements are more specific, but should not be ruinous.

Large businesses will invest millions in their compliance work hiring large in-house teams to deal with regulators in each market and using leading outside counsel from the global law firms they employ.

There will be regular challenges to the policies and practices of large companies that mean they have to update their documents and tools continually which they will do with big cross-functional teams.

There may come a point where the regulatory demands in a market cause a large company to question its presence there but it will usually find the resources, even if irritated by this, to maintain its overall global presence.

Where we may see the biggest change is with medium-sized entities who are big enough to attract attention and so have to take compliance seriously but who do not have the abundant resources of the internet giants.

These entities may find that decisions about whether or not to be in a particular market are more finely balanced especially where the risks seem to be high, eg threats of large fines or criminal action against execs, and the entity does not feel it is fully across them.

We may then seen mid-sized companies confining their operations to a restricted set of relatively safe and lucrative markets while opting out of ones where the risk-reward calculation falls the wrong way.

This in turn would mean fewer services for consumers and less competition for the large established players in non-core markets.

There are no easy solutions here if you believe that regulation is important to protect people and that it should be comprehensive, in terms of both the range of entities and types of content covered, but it is better to consider likely market impacts now rather than be surprised by them later.