The heated debate going on in the US about postal voting prompts me to reflect more widely on voting mechanisms and the use of technology.

This is not strictly speaking about the regulation of tech so much as about how tech can be used in a political context, which I hope seems like a reasonable (and interesting) tangent to follow for this blog.

I should say at the outset that, despite being a techie, I have been quite sceptical about online voting as I worried about people coming under undue pressure as they cast their votes (which is an issue for all forms of remote voting).

But, as I reflect on how tech has moved on, and consider the pros and cons of each method, online voting has a lot to offer and should play an increasingly important role in elections.

Voting System Design

We should first consider the core goals of any system for voting, which are :-

- that the preferences of all people who are eligible and wish to take part in an election are correctly recorded;

- that this happens before the deadline that has been set for the election;

- that people are free from ‘coercion and undue influence’ when they cast their votes; and

- that the votes cast by each person are kept secret.

I am not going to talk about eligibility and voter registration in this post – that is a complex subject that merits its own separate consideration.

I am also not going to talk about the counting of votes, and in particular whether machines can do this reliably, as that is again a complex area with its own expert commentary.

I am rather going to look at the different mechanisms people might use to cast their votes and consider how they match up to these goals.

Whose Election?

There is a risk that we see the candidates as being the most important stakeholders in an election, and politicians may feed this impression by noisily opining on how elections should be run.

But elections are not held for the benefit of candidates.

And voting system should be designed in the service of electors, who are the most important people here, and not in the service of parties or candidates.

Most politicians will say that they want to see maximum turnout at elections in the interests of democracy.

Some of them will be sincere when they say they would rather see a high turnout and lose than win on a low turnout.

But these are the exception as the raison d’être of a politician is to win, and, more typically, they will privately be happy if only ‘their’ people turnout while the opposition stays at home.

We see this in political campaigns which are geared towards identifying your own supporters and relentlessly pushing them to turnout while, at best, ignoring voters who they have identified as being on the other side.

When campaigns launch attacks on other candidates or parties, they know these are unlikely to convert many voters to their side but the attacks serve to demotivate the other side’s voters making them less likely to turnout.

In short, politicians cannot and should not be given a free hand to decide on voting systems given this inherent conflict of interest.

Politicians have to be involved in creating the regulations for elections but the greatest weight should be given to the views of independent experts and regulators, and groups that represent the interests of electors.

Place, Post or Click

There are three methods that can be used to register votes in a modern democracy (I assume that older methods like public shows of hands or scratching on pot sherds are gone for good) :-

- you fill in your ballot at a specific polling place that has been established by the election administrator;

- you complete a ballot paper that the election administrator has sent to you by post and return it to them by post;

- you register your vote on an online system that the election administrator has built and given you access to.

These systems are in use in different combinations in countries around the world including a number who have implemented online voting.

An optimal system would likely want to include all three methods if its goal is to serve electors, as each of them will be preferred by different groups.

There may be cost or other reasons (such as an epidemic) for not offering all options at all times, but we should be careful not to argue that a method is bad if it has been rejected on cost rather than quality grounds.

We can look at the pros and cons of each method by considering the following questions :-

- Secure – is the person casting the vote the one who is registered and entitled to do so?

- Convenient – does the elector find the system easy-to-use considering their personal circumstances and preferences?

- Free – is the elector able to cast their vote freely, without coercion or undue influence affecting their choice?

- Secret – can an elector be confident that other people will not be able to associate their choices with their personal details?

- Trustworthy – does the method of voting increase or decrease the confidence of electors in the eventual outcome?

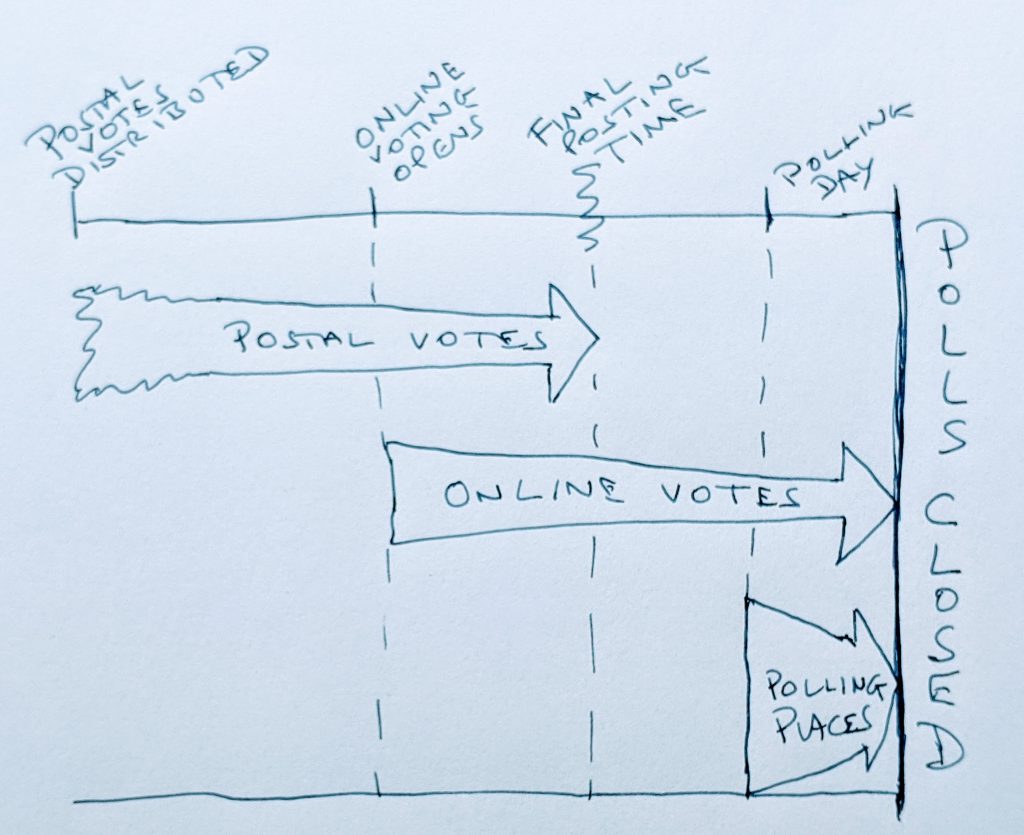

The timelines for how each method can be used are also important.

Polling place voting usually has the shortest window (though some countries open polling places over multiple days).

Postal voting typically requires the longest window so ballots can be sent out and returned, and there may be significant variation in when post arrives or has to be sent according to local vagaries of the postal service.

Online voting can be ‘turned on’ at a specific time as determined by the election administrators and kept open up until the precise moment that the polls close.

Polling Places

Voter verification systems vary between countries and many do have checks in polling places.

In the UK (except for Northern Ireland), there is no identity verification in the polling place and ballot papers are provided to people who give a name and address that is on the register for that locale.

The defences against abusive voting lie in the overhead of making repeat visits to polling stations without being spotted and the risk of criminal prosecution.

For some people, attending a polling place is convenient and they may enjoy the performance of going and casting their vote (I count myself in this group).

For others, especially for working age people where polling happens during the working week, it may be highly inconvenient.

Where polling places really shine is in supporting votes being cast freely.

They are designed to create a protected space in which an individual can make their choice without anyone being able to see it.

The experience we have in the UK today was created precisely to mitigate against the risks of coercion and undue influence that were seen as problematic in the past.

The polling place is now a hushed place protected from campaigning and with its particular setup of curtained booths and stubby pencils – a strange crossbreed of a public library and IKEA.

Polling places also score highly for secrecy – there may be ways to trace votes back to individuals later, but the act of placing the paper in a box breaks the link between it and the voter in the instant of voting.

A weakness of polling place voting is that it does not offer strong mechanisms for individuals to audit and therefore trust the process.

In countries where there is a high degree of confidence in the officials who oversee polling places this may not be a major issue.

Critics of postal voting in the current US debate seem confident about the integrity of polling places though there are claims about ballot box stuffing from time to time even in the US.

We can contrast the US situation with the recent election in Belarus where concerns very much centre on whether the results that came out of polling places tally with the votes that went into them.

For people in Belarus, polling place voting certainly does not create trust and an online system that provided voters with copies of the votes they cast might create a higher degree of confidence.

Postal Ballots

For postal ballots in the UK, the checks have been enhanced over time so that there would be a significant overhead for anyone today trying to send in multiple fraudulent ballots.

This was not the case when I started out in politics in the 1990’s – it was relatively easy then for people to request and return multiple postal votes, eg for all the residents of a care home, and this used to happen.

There may still be a sense postal vote fraud carries a lower risk of prosecution as the crime is not being committed in front of witnesses as it would be in a polling place.

But any attempt to cast fraudulent postal votes at scale is likely to trigger some kind of investigation and there have been successful prosecutions.

With robust enforcement focused on holding candidates and parties to account for the fraudulent use of postal votes, the risks can be managed, and have been for many years in countries around the world including the US.

Perhaps more concerning than vote-stealing are issues around protecting postal voters from coercion and undue influence.

It is not hard to imagine scenarios where a dominant member of a household stands over their family instructing them on how to fill in their ballot papers.

This risk is there to a degree for all voting methods but the polling place is most protected (if the voter is willing and able to lie to the family member trying to direct their vote).

It would also be possible for someone to seek to ‘buy’ postal votes by offering inducements to voters willing to fill their paper in as directed.

Again, this is true for all methods with the difference for polling place voting being that the voter could take the inducement, vote differently and then lie about what they did in the secrecy of the voting booth.

Technology is limiting this freedom though as those determined to direct other people’s votes may ask them to take a photo of the ballot paper to prove they have followed instructions.

A great strength of postal voting is the convenience for many people both because it can be done from home and because it typically creates a longer window in which to cast your vote.

This convenience is reduced for those who are not regular users of the postal system and so unfamiliar with posting box locations etc and for those who live in areas that are not well served by the postal service.

Postal ballots are inherently less secret than in person voting in that they necessarily mean that for a period of time a ballot paper is associated with the details of the voter.

This may be only for the period while the vote is in the post if the system verifies identities and then separates off the ballot papers immediately on receipt.

Important safeguards here are strict rules around the handling and storage of unopened postal votes and effective sanctions against anyone who breaches these.

In terms of trust in the outcome, postal votes present different weaknesses from polling places.

The risk that particular polling place staff are fraudulently stuffing ballot boxes is mitigated as the votes go directly to the election administrator.

But postal votes do not provide a good audit trail for individual voters as there is typically no confirmation back to the voter that the vote has been received.

There is some risk around the postal service being either corrupt, ie employees tamper with votes, or incompetent, ie they do not deliver votes as addressed.

We are left with a case of ‘choose your points of failure’ between polling places and postal services, with both capable of delivering a good and reliable service if well-managed, and both open to potential malpractice if not.

It is possible for people to mitigate these risks to some extent, eg taking photos of all the documents and making records of each stage but this is labour intensive and still one-sided.

As we see in other areas of life, the switch from paper post to digital communications provides much better feedback loops for us to understand who has seen things when, and this may be a ‘killer feature’ in favour of moving to online voting.

Online Voting

A shorthand way to consider online voting is that it is a ‘better’ way of doing postal voting.

The most important issue to consider, as we need to for all forms of remote voting, is that voters may be subject to coercion or undue influence.

There were experiments with online voting in my constituency in the UK in the period 2001-3 and I was sceptical at that time precisely because of this coercion risk.

The picture I had in mind then was of people voting using a desktop family computer with an assumption that this device may be largely controlled by one member of the household.

Anyone who has campaigned by knocking on doors at election time will be familiar with the phenomenon of one person (generally an older male) answering the door with the declaration that “we all vote for party X in this house” while other family members standing behind them discreetly signal that they will be voting otherwise.

It seemed reasonable to fear that a move towards households voting using a computer controlled by one person might make it harder for people to vote according to their individual preferences.

In 2020, the fact that most people have online access through their own personal devices helps to mitigate this risk (though of course people can still stand over others as they vote by phone).

Phones also significantly help in ensuring that the person casting the vote is the authorised person with the now widespread use of 2 Factor Authentication using SMS or authenticator apps.

While there are always ways round security systems, it is much harder for anyone to cast fraudulent votes at scale when they have to, eg clone SIM cards to get verification text messages, rather than just being able to use lists of login IDs and passwords.

In terms of secrecy, online voting systems will mean that votes are associated with personal ID’s for some period of time, at least during transmission to the election administration system.

But systems can be designed to make any such association much more fleeting and transitory than is the case for postal votes, and they can use anonymisation techniques for data in transit that are not available for paper documents.

The extent to which individuals would find online voting convenient will vary depending on their level of technical competence and connectivity.

But we can reasonably assume that for a significant percentage of electors in 2020, online voting would be more convenient than either polling place or postal voting, and this percentage is likely to keep growing over time.

Where online voting scores especially well is in terms of the verification and audit capabilities it can offer to the elector.

Online voting systems can be designed to confirm the receipt of your vote instantly.

Importantly, systems could provide voters (if they want this) with a verifiable record of their vote.

This would raise important questions around ballot secrecy but also has huge potential for enabling new forms of election audit.

In situations like Belarus, people might share verified records of their votes (with their consent and appropriate anonymisation techniques) with a non-governmental election monitoring organisation.

Online voting systems would also produce transactional data – not who people voted for but when votes were cast and where they were coming from – that can help with integrity and trust.

Looking at current US debate, while concerns about postal voting security are being hyped up for partisan reasons, the best way to mitigate these for future elections is an online system with audit trails, receipts, personal copies etc.

This would need thoughtful design as it must not be about forcing anyone to give up the secrecy of their ballot, but about giving electors more tools that they may choose to use to verify the outcome.

Casting One Vote Several Times

Online voting also has the potential to offer electors the ability to change their votes as the campaign progresses.

A weakness of postal voting from a decision-making point of view is the long lead time that it requires to guarantee ballots can be returned before polls close.

An election period is intended to inform voters about the various choices on offer before capturing their views through their votes.

This dynamic is changed when people are voting before the campaign has run its course – this is a feature of all early voting systems but is especially acute for postal voting because of the pressure to get ahead of the cut-off several days before polling day.

While many voters are settled in their views early in the campaign, there are instances where public sentiment moves significantly in reaction to information that comes out very late in a campaign.

Of course, new material may also come out after polling day and all cut-off dates are to a degree arbitrary, but if the polls are still open and yet there is no way to change a vote this can cause particular frustration.

Offline systems can cater for this by allowing people to cast an in-person vote that would supersede their postal vote but this is cumbersome to administer and requires the person to get to a polling place.

Online voting systems could be designed to allow people to record their vote but still be able to change it right up until the close of polls.

We can imagine a system that asks you whether your vote is final or provisional.

If you choose to make your vote final then it is submitted immediately and the link is broken with your identity.

If you choose to make your vote provisional then it is recorded as your preference but you can come back at any stage to change it and again decide whether this is a final or provisional vote.

Provisional votes would automatically become final and get submitted at the moment when polls close.

A feature like this would carry additional secrecy risk in that provisional votes would have to remain tied to the voter’s identity until they are finalised when the link could be broken.

But this may be considered a reasonable risk to take when traded off against the benefit of being able to change your mind right up until the close of polls.

Where Next?

The US debate pitching Polling Places against Postal Voting presents us with a false and distracting choice.

Both systems are fine as far as they go, but if we want to improve things for electors (including their confidence in outcomes) then we need to make progress with online voting.

There is a good base of research and data looking at the technical performance of different voting systems around the world including from countries like Estonia that have used online voting for some years.

Scholars like Prof Stephen Coleman have also carried out fascinating research into how people feel about the process of voting that can help inform how we think about new voting systems.

There may be structural challenges to rolling out new systems in countries, like the US, where election administration is highly localised but this should not be an excuse to fail to serve electors better.

I vote to cast my vote online!