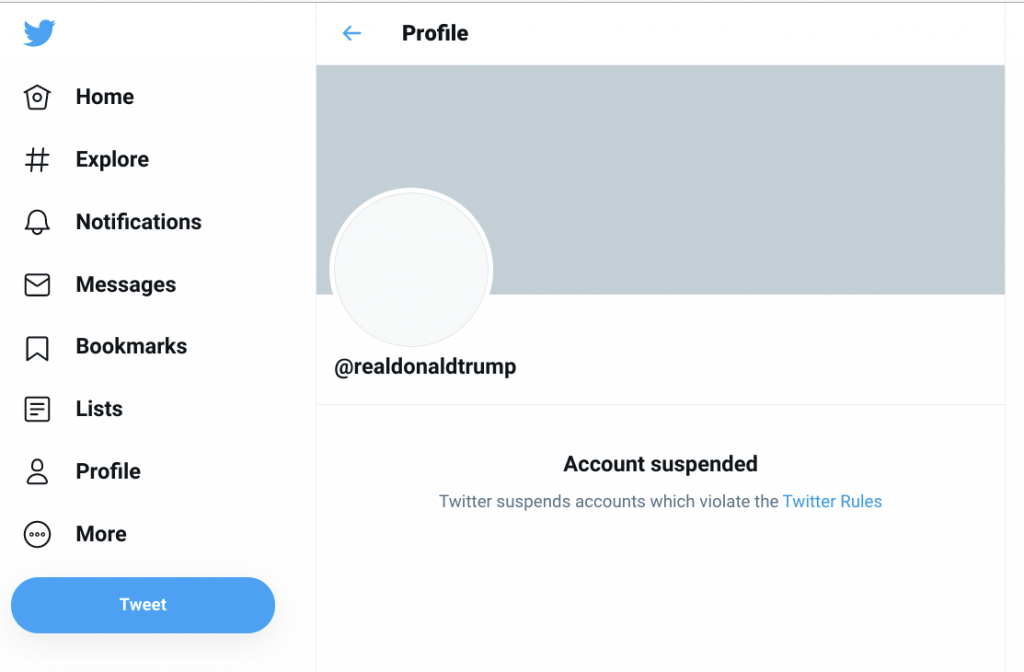

So, some platforms have said outgoing US President Donald Trump can no longer operate an account on their services, and the debate over who gets to make decisions about online speech has shifted into overdrive.

A common refrain in this debate is that the removal of Trump’s accounts shows that platforms are exerting ‘editorial control’ and so should be ‘treated like other publishers’.

In this post, I want to build on something I wrote last year digging into what platforms and news publishers actually do and how these are quite different beasts.

When news media are exercising ‘editorial control’ this is primarily a ‘selection’ function, where the staff of the publication decide which people and content to include in their website, newspaper or broadcast program.

When social media (and similar user-generated content services) are exercising ‘editorial control’ this is primarily an ‘ejection’ function, where the staff of the platform decide what content and speakers to exclude from their website.

[NB There are other ‘selection’ questions related to how platforms recommend content, but here I am using the term to refer to the selection of who gets to speak at all which is very different for social and news media.]

Each of these functions can have a profound effect on the public debate, so they are both important, but that doesn’t make them the same and, when it comes to regulation, a regime designed for one will just not work for the other.

Different Types of Clubs

An analogy may help illustrate the difference between these functions and understanding of why it is important to treat them differently.

We can think of the news media as being like a private members’ club, while social media is more akin to a football club.

The people who get access to a private club are its members, who have been pre-selected to meet the club’s membership criteria, and their invited guests, signed in and vouched for by a member.

These selection and sponsorship systems are usually a powerful means of enforcing the club’s rules on members and their guests.

If a guest causes trouble, then the club would hold the member accountable and, knowing this, members are expected to choose their guests with care.

By contrast, the grounds of a football club are normally open to all comers (if they have tickets) without any pre-selection or need for an invitation.

People come in their thousands and the club management may have little or no information about many of the people who come to their matches.

What the club may do, if someone abuses the privilege of having open access to the ground, is seek to eject them from the ground either just that day, or with some kind of long term ban in more serious cases.

Editing in a News Media ‘Club’

As with a private member’s club, there is no public right of access to speak on a television program or be quoted in a newspaper story.

The only people who get to speak through the news media are ‘members’ – journalists who have been previously selected by the outlet – and their ‘guests’ – those who have been invited to make a contribution by the journalists.

A news media publication will normally feel responsible and accountable for the actions of its staff and guests and will select them carefully with this in mind.

In most cases, a news media ‘club’ will have wide discretion over who it selects as journalists and guests with no third party able to order it to give a platform to specific individuals.

A news media outlet can often decide exactly how much, or how little, exposure it wants to give to any particular political figure and their supporters, including never inviting them on at all.

[NB In some countries, specific classes of news media outlets may have to comply with political neutrality rules either generally or at election time and this will shape their selection of guests, while outlets outside of these regulated classes and/or times can be as partisan as they like.]

Editing in a Social Media ‘Club‘

Social media services are generally offered to the public without pre-selection over who can sign up, beyond having an email address or phone number, not least because their success depends on scale.

Anyone who has signed up can speak on social media, and individual users are expected to feel accountable for their own speech and actions.

Where someone breaks the rules of the social media ‘club’, its management may deal with the specific offence (remove their violating content) or eject the individual (close their account) so that they are no longer able to use the platform.

We see then that the real power that these platforms have is one of setting the rules and ejecting those who break them rather than one of selecting who gets to be on there in the first place.

Who Gets To Push The Eject Button?

This power of ejection is different from traditional notions of media editing, but can still be a mighty one, and the question of who gets to wield it is worthy of debate.

The choice is often framed as an either/or one – these decisions are either going to be in the hands of some kind of public authority, or they will be left to private companies (typically personalised to their CEOs, so it is ‘Mark’ or ‘Jack’ who are calling the shots).

Our football club analogy can again be useful here in providing a model where these are actually ‘both/and’ decisions.

In the UK, there is a legal provision for ‘football banning orders’ where the Courts prohibit someone, typically a serial or serious offender, from entering football grounds for a period of time.

This is an example of the public authorities taking ownership of an ejection decision, and it provides a framework for the banned person to challenge their ban through judicial processes if they believe it is unfair.

But the existence of these court-ordered bans is not a replacement for the day-to-day work of keeping things orderly within a ground, and clubs can also eject people where they believe this is necessary, whether or not they are subject to a legal order.

This dual approach where both the private entity managing a public space and the public authorities might eject someone, depending on the nature and severity of the offence, is the norm for many places where people congregate, rather than this power being entirely held by just one of the parties.

Social Media Banning Orders

The first question for regulators is then whether and how they would want to impose their own ‘social media banning orders’.

These bans already exist in some jurisdictions for specific offences, for example people who are convicted of child sexual abuse or terrorist crimes in the UK may be banned from using some or all internet services, but they are a heavy instrument that may not be proportionate for other types of abuse.

There may also be a timeliness issue for bans that have to go through formal legal procedures, with delays that can be for good reasons if the intent is to have a fair process.

For example, in the area of terrorism, we see new groups springing up all the time that would meet most people’s definition of being violent extremists, but it can take months or years to update formal government lists of proscribed organisations.

If we were to have a regime where only groups named on official lists could be banned by platforms, then the price of this would be to allow some dangerous organisations to maintain an online presence for much longer than at present.

From a due process point of view, you may feel this is reasonable and that tying bans to government proscription would make governments get their act together and move more quickly to assess and prohibit organisations.

It would certainly be helpful to aim for consistency between government and platform lists of banned organisations, but I am not persuaded that there can ever be full alignment.

There is a major challenge in agreeing global standards for what constitutes a proscribed organisation, and without these, platforms will be left trying to reconcile their lists with many lists of varying reliability in terms of human rights standards.

It also seems likely that there will be a persistent class of groups and individuals who are dangerous enough for platforms to want to ban them, but not so dangerous that they meet the criteria to be proscribed under anti-terrorism legislation with the massive consequences this entails.

Government Overrides

If you accept that in general there will be this dual approach, with platforms able to make their own decisions on ejections, then you may still feel that there has to be an override where public authorities can order that someone is let back on to a service.

This has been floated by a number of policy makers over the years and the Polish government has a proposal along these lines which is attracting attention at the moment.

We should recognise the political motivations that can sit behind proposals like this – the right wing Polish government is irritated with Facebook for banning nationalist groups and individuals that it sees as its supporters but which Facebook has determined are dangerous enough to be ejected.

This threat of legislation is intended to persuade Facebook to ‘go easier’ on these groups unless it can show they are definitively in breach of Polish law.

Meanwhile across the border in Germany, we have a centrist coalition government that is trying to fend off a threat from new far right forces, and it has enacted legislation with the intent of encouraging Facebook to be more aggressive in removing the kind of people that the Polish government appears keen to defend.

Both the Polish and German governments will, I am sure, claim that they ‘just want platforms to follow their legal standards’ but they do so with a clear political interest in the effect this may have.

The Polish government is confident that Polish law will help ‘their people’ keep a presence on platforms, while the German government is confident that German law will force platforms to crack down more on their political enemies.

They may both be following legitimate aims in political terms, and you may support them on the grounds that governments should decide these things, but they reflect political expediency as much as they do any higher principle.

Must Carry and Liability

There is a longstanding concept in broadcasting regulation called ‘must carry’ provisions where a distribution platform is required to carry certain channels as a condition of its license.

Different countries have varied criteria for when they will impose these obligations but the core rationale is that there is a public good in people being able to access certain channels, and it is not for those who own capacity-constrained distribution channels to decide to drop them.

You can see echoes of this rationale in the argument that there is a public interest in being able to access the views of people like political leaders and so platforms should not have any discretion over whether to ‘carry’ them.

There is a wider debate about the extent to which must carry provisions, which were necessary at a time where broadcast capacity was limited, make sense when the internet offers effectively unlimited capacity, but let us for a minute assume this concept does get rolled over to social media.

We would then see a regulator ordering platforms always to allow certain individuals or organisations to maintain an account, based on criteria defined by the regulator, for example because they hold a particular office.

In this world, where regulators are able to order services to permit particular people and organisations to have a presence, questions of platform liability become very important.

To go back to our football ground, the comparable situation is where a club wants to expel someone it believes to be a troublemaker but is ordered by some higher authority to let them back in.

Most of us would consider that it is not reasonable to hold the club responsible in these circumstances if the person they were told to let back in goes on to cause the trouble they feared they would.

As a matter of fairness, we might then expect to see a clear commitment to not holding platforms liable for any harms caused by someone they were ordered to carry, whatever the broader liability framework may be.

Section 230 (again)

The US offers broad liability protections under the famous Section 230 (of the Communications Decency Act) so it would seem that platforms could protect themselves against claims related to anyone they were required to carry under this existing regime.

But one of the ironies of the current situation is that President Trump’s own threats to remove these protections are an important part of the process that has led to the removal of his accounts.

A case is being built to reform the law based on examples of situations where platforms should (according to the court of public opinion) have been held liable but were not, and the example of their allowing President Trump to tell lies that foment discord is often cited as just such a case.

So while platforms could likely defend themselves today against people suing them for responsibility for violent disorder because they provided a platform for the instigators of the violence, each time they fail to act this is seen as an argument for opening up the door to just such suits by scrapping Section 230.

We also need to recognise that broad liability protections like Section 230 do not exist in many other parts of the world.

In the EU, platforms may become liable for online harms as soon as they are notified about them, and could face a significant legal dilemma if they were not able legally to eject someone who is causing harm.

There is a trend towards imposing obligations on platforms to remove harmful content swiftly once they have been notified about its presence, which could directly conflict with obligations not to interfere with the accounts of certain people or organisations.

This could be resolved by ensuring the rules against online harms all have a coda to say ‘except where the harm is being committed by a protected person’ but this does not sit well with the notion that harm prevention is paramount.

Sinners Who Repent

After that tour around the some of the issues raised by platforms and governments ejecting people from services, I will close on a more positive note with some thoughts on redemption.

If you believe that a form of speech is causing harm, then evicting someone may not stop the harm but merely move it elsewhere.

In the case of the current situation in the US, we see a societal harm in its most acute form in the riots in Washington DC, but also in a more chronic form in the ongoing lack of confidence in elections and legitimacy of US leadership.

Ejecting people who are causing this harm may be necessary to address the immediate threat but it is not the best way to improve matters over the longer-term.

What we should be hoping for is that President Trump is prepared to recognise that the election was free and fair and that Joe Biden will be the rightful and legitimate President of the US from next week.

And if President Trump were to do that then there would be a good case for platforms to consider allowing him to use their services again.

Of course, there are other accountability processes in play, and I am sure there would be questions about the sincerity of any apparent change of heart, but an outcome where someone publicly moves on may be most effective in addressing the harm and this should be weighed in the balance with other equities like deterrence and punishment.