We can expect lot of the discussion about new regulatory frameworks for online services in 2021.

Much of the debate will focus on the mechanisms for regulating platforms – who will be the regulatory body, what penalties they can impose, how broad their remit will be etc.

This is natural and I expect that I will also spend time on these questions as the UK proposals work their way through the legislative process.

But today I wanted to take a step away from the details of the law and consider WHAT a new framework might deliver rather than HOW it will do this.

They Work For Us

Our starting point should be that both online services and regulators work for us – as consumers of the services, and as citizens interested in the well-being of our societies.

We have a right to ask platforms to deliver what would be most useful for us, as their customers, and we expect regulators to hold platforms to account for meeting our demands.

It is a commonplace that not every consumer of particular services will have a fully formed view of what they want, and there will often be differing opinions of what services should be asked to produce across a diverse population.

This is where Parliament and the Executive come in – it is their job to understand the diverse range of people’s interests and the different requirements that could be imposed on services, and to distil all of this into a workable and effective scheme that can be set out in legislation.

Tell Me What You Want

I have been thinking for some time about what I would want as a citizen, and have refined this based on my understanding of what would be possible from my experience in the worlds of technology and politics.

The ‘product’ that I believe could be most useful here are documents that I have called ‘Harm Reduction Plans’.

Each plan would provide any of us who are interested in these matters with a clear and easily intelligible description of how a platform has assessed the risk of a particular harm and what specifically it is doing to combat this harm.

These plans would form the basis of the engagement between the regulator and platforms, with the regulator able to test each aspect of the platform’s understanding of the problem and proposed response.

There should be published versions of the plans that contain sufficiently detailed information for us all to understand what is happening, while some information may be provided only to the regulator if it is especially sensitive.

The harm reduction plans from the platforms would be complemented by responses from the regulator setting out their assessment of the information they have received.

For example, a plan may inform us that a platform has exposed the criteria it is using when it scans for certain content types to audit by the regulator, and the regulator response will tell us whether they think these are reasonable.

A Template And An Example

This can best be illustrated by working through an example harm reduction you can download here :-

[NB I have written the example plan as though it were being presented to the proposed UK regulator, Ofcom, but would expect platforms to produce local versions of their plans in countries where they have a meaningful presence.]

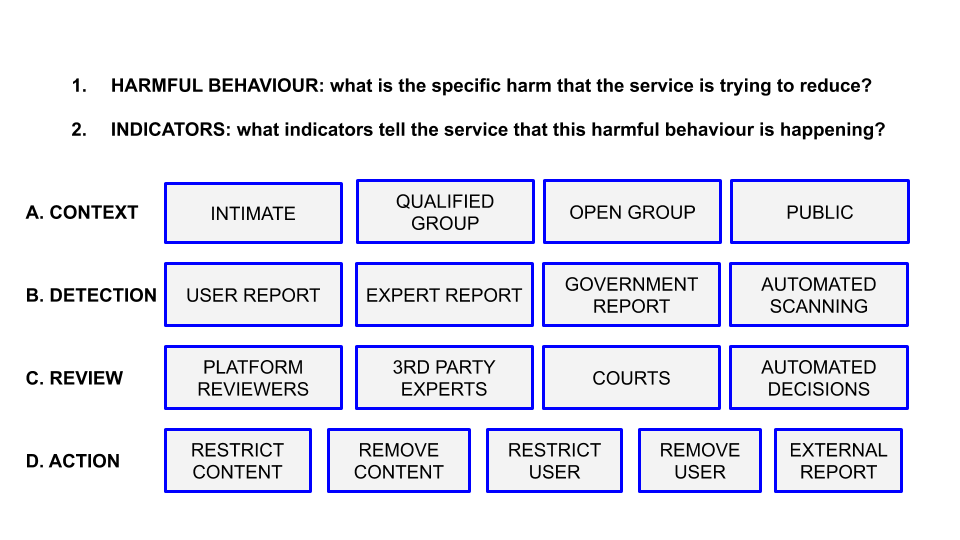

The plan is based on a template that I have set out in diagrammatic form :-

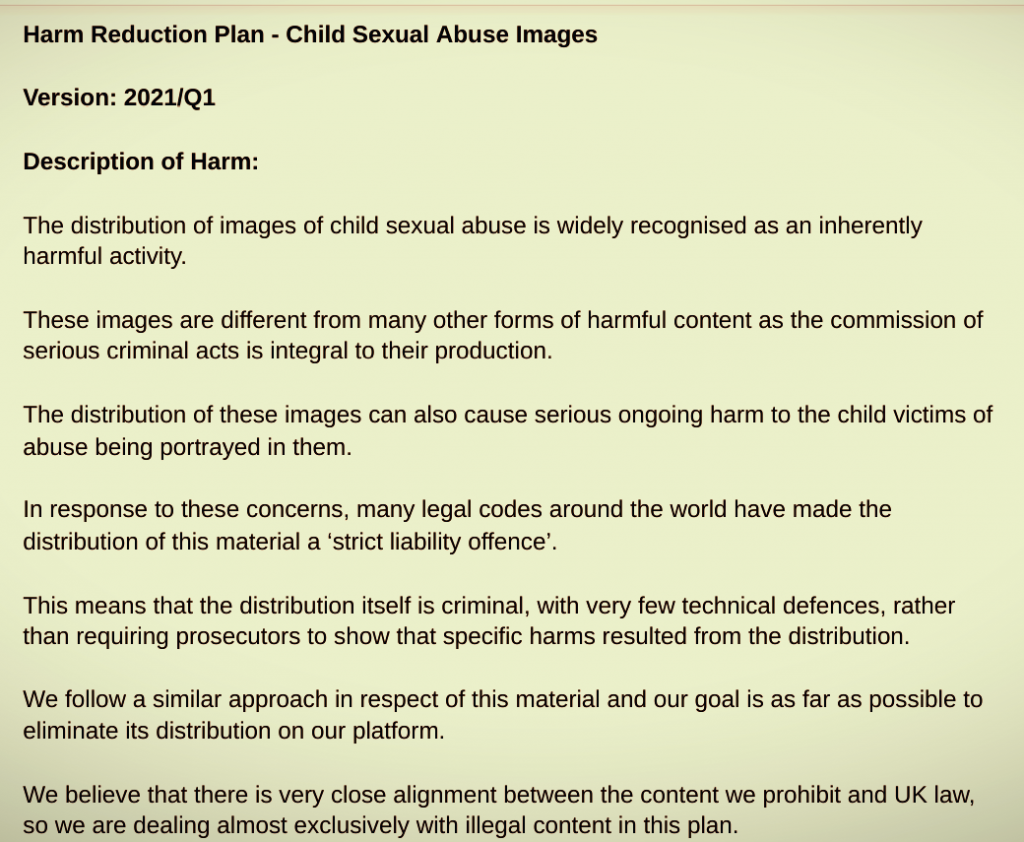

The first thing we need to do is to describe the harm in detail with an emphasis on explaining the rationale for why a particular form of activity is deemed to be harmful.

There may be a temptation to assume that everyone knows why online activity is problematic so we can just refer to the type of content and leave it at that.

In my experience, people are often working to different assumptions about how and why something is harmful, and as a result may reach different conclusions about the appropriate response to it.

If we start each plan with an explanation of the platform’s thinking on a particular harm then this will help us to understand their proposed manner of dealing with it.

These explanations are of course contestable and some of the most significant debates between platforms and regulators may be over how a harm should be viewed before we ever get on to counter-measures.

In this example, the platform makes it clear that they see the distribution of this material as always harmful and explains why this is the case.

I would expect this to chime with the regulator’s own view in this instance as there is a broad consensus in the UK about the harms caused by any and all distribution of child sexual abuse images.

In other areas such as hate speech or misinformation, there might be much more debate about the specific ways in which this content is harmful to individuals and society, and the rationale for platform interventions.

The description should also make reference to the extent to which the content being covered in the plan is illegal in that country.

For child sexual abuse images there is likely to be close alignment globally as most countries make this material illegal, though there may gaps between standards and the law in some details, for example not every country includes hand-drawn or faked images in their definitions of illegal content.

When we draw up plans for hate speech, we are likely to see the overlap with illegality vary quite widely from countries like the US, where this content is generally entirely legal, to countries like Germany that criminalise a broad range of speech on the grounds that it is hateful.

In the case of the UK, most of the hate speech content that platforms remove would not meet the standard for criminal incitement so would be described in the plan as ‘harmful but legal’.

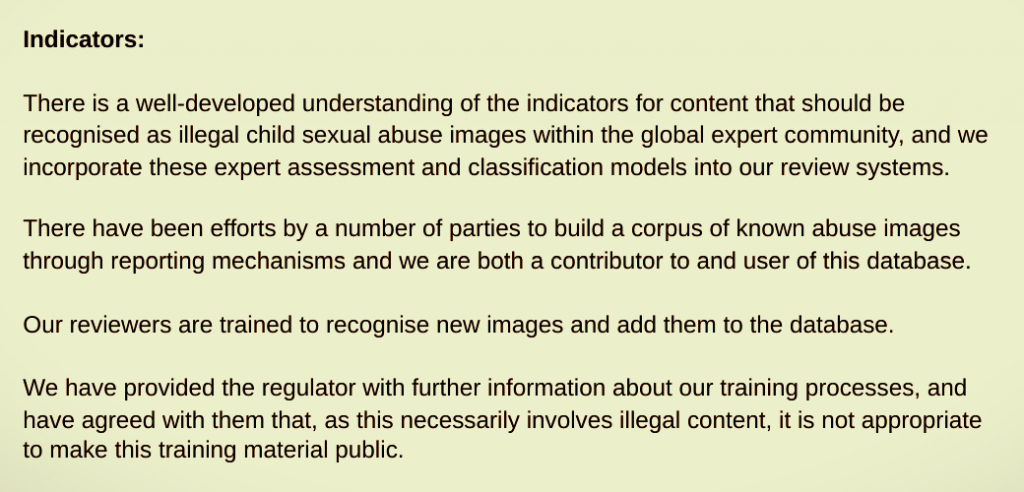

Indicators

We next need to set out the indicators that the platform is using to define the behaviour that is causing harm.

There may again be a temptation to assume everyone has a common understanding of what ‘bad’ looks like, but spelling this out helps us to test that assumption and be precise about what the platform is trying to catch in the plan.

In the case of child sexual abuse images, the plan can refer to a well-established set of definitions that experts and government agencies use in their work.

There is also a database of images that is shared between platforms and government agencies and actively used within detection mechanisms.

The nature of the material in this case means that reference material cannot be made public but may be discussed in secure conversations between platforms and the regulator if there are any concerns about scope.

For other areas where the content is not inherently illegal, it would be preferable to make reference material available so that there is a shared understanding between the platforms, regulator and public about what is being classed as harmful.

In my experience, this is especially an issue for hate speech where there can be wide variations in what people feel the indicators should be, with many people including forms of ‘hateful’ speech whether or not it attacks minorities.

After defining the nature of the harm in these first two sections – Description and Indicators – the rest of the plan takes us through the different ways in which it is taking steps to reduce that particular harm.

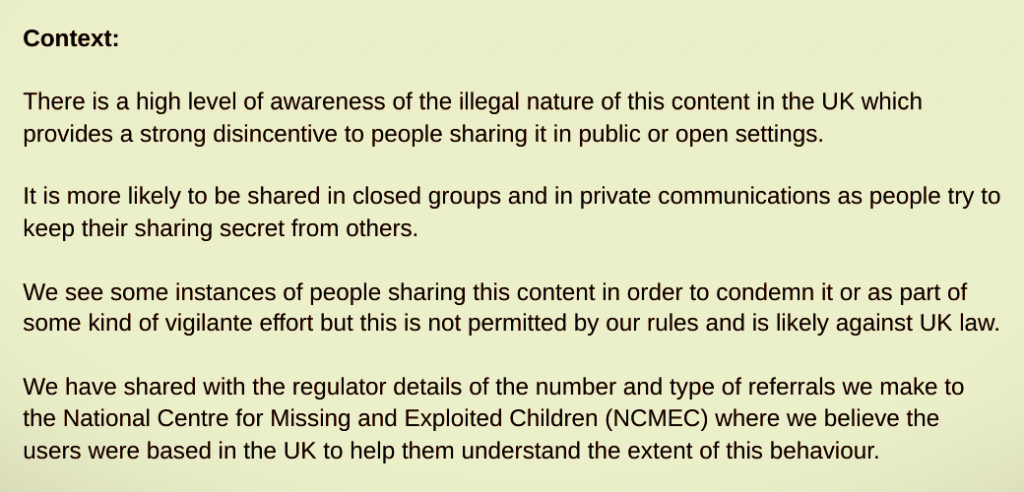

Context

We first need the platform’s assessment of the contexts in which the harm is occurring as this will condition the kinds of intervention it will make.

I have suggested in the model that there are four types of settings where online activity may take place, though not all of these will be relevant for all services.

Intimate – this refers to 1-to-1 communications or those with a small group of people that are close to you – we can think of family and personal friend groups here – with connections typically in the single digits or tens at most.

Qualified Group – these are activities within a group of people who are all part of an organisation – groups of work colleagues, sports association members, professional bodies, academic interest groups etc. These groups are not open to just anyone to join – but people are rather ‘qualified’ to join by their connection to a specific entity. Their memberships will typically be in the tens or hundreds.

Open Group – these are groups where anybody can join without any pre-qualification. For example, I might be a member of a forum about Sheffield, my home town, that is open for anyone with an interest in that city to join. The memberships of these open groups will typically be in the hundreds or thousands, and may reach millions in the case of very popular fora.

Public – these are communications that are open for anyone on the internet to see and the intent of the content publisher is for their content to be viewed by all, for example public videos on YouTube, tweets on Twitter, and posts on public Facebook pages. The potential audience for this content is billions, while the actual number of viewers will vary widely according to popularity.

There will of course be many instances where activity does not neatly fit within these boundaries, but they provide us with a framework to think about content in terms of intended audience.

To wrap this into a single question, we can ask whether the harmful activity takes place within or is directed towards :- a) a small group of intimate family and friends, b) a defined group of people in the same organisation as themselves, c) a wide group of people who they do not know but with whom they share a loose common interest, or d) the whole world?

Thinking about context is important to understand the effects of the harm, which may vary according to how and where a behaviour is taking place.

Platforms also need to understand context to decide which methods of detection are useful and appropriate for particular types of harm.

We might expect there to be a strong focus on activity within intimate and qualified group settings in a plan for child sexual abuse images.

People may also distribute this type of content in open groups and public settings so everything is in scope but there will be a particular concern about people using more private spaces in an attempt to avoid detection.

By contrast, a hate speech plan might find that people are much more willing to share this content in public spaces, and it will have a greater focus on public content that many people are likely to find threatening.

A hate speech plan might also include scanning of content in closed groups, as these are potential sources of dangerous extremism, but decide against looking at the language people use in their intimate communications where this has not triggered a complaint.

Detection

The next question for the plan is for a platform to consider how it can find out whether a harmful activity is taking place?

It is common for platforms to offer users the ability to report problematic behaviour to them.

These systems can range from the providing a simple abuse@ email address through to sophisticated multiple choice contextual reporting forms.

User reporting systems may produce a high ratio of ‘noise’ to ‘signal’ as people use them to try and get the attention of the platform to anything they dislike, whether or not it relates to a real harm.

People may report their concerns to local bodies like specialist NGOs and government agencies, and these organisations can also carry out their own proactive investigations into harms within their spheres of interest.

Platforms will usually need to develop some way to receive and respond to reports from these external bodies in countries where they have a meaningful presence.

Platforms may want to prioritise these reports as they are likely to have a high signal to noise ratio where the referring body has the capability of making expert assessments and accurately identifying harmful behaviour.

In the example plan, the platform describes the relevant user report options it offers, as well as the relationships it has with external bodies and the arrangements it has made to respond to their reports.

I have given single examples here but we might expect to see platforms engaging with a long list of relevant agencies in countries where they have been established for a while.

The regulator may find it useful to solicit feedback from the local agencies that work with a platform on how responsive and effective they find them to be as part of its assessment of a harm reduction plan.

There may also be survey data available on how users experience the reporting systems offered by a platform that will help the regulator in its consideration of whether the platform is providing the right tools.

Reports from users and external bodies are a form of ‘post-moderation’, ie they involve someone noting the problematic content or behaviour after it has happened and asking the platform to look into it.

Platforms might also carry out ‘pre-moderation’ via manual or automated means, ie identifying and reviewing content before it has been reported as problematic by anyone else.

Full-scale manual pre-moderation of all user-generated content on a platform has generally been seen as unfeasible – the volume of user-generated content is simply too high to look at everything – and this remains true.

But it has become increasingly possible over recent years for platforms to identify potentially problematic content using automated methods at massive scale and these are likely to feature in many harm reduction plans.

These may be entirely automated processes, where machines identify, review and action content in a single flow, or they may involve manual stages so that machine-identified content is passed to a human for review and action.

When, where and how to use automated scanning is likely to be a key part of the conversation between regulators and platforms as they try to define what it means to be a responsible provider of internet services.

The example plan tells us that the platform is carrying out extensive scanning to detect child abuse images across all public and private contexts.

This reflects the relative maturity of these systems, which I have described in a previous post, and the importance of preventing distribution of this material by any means.

We might see more explanation of how the systems work for other content types such as hate speech where there is is a need to discriminate between uses of similar language that may or may not be hateful.

Platforms may also decide not to deploy automated scanning in some contexts and would need to explain these decisions in their plans.

In some cases it may be appropriate to share extensive information about how the automated tools work and their performance publicly while in others detailed information would be provided to the regulator only for their audit.

Review

In most cases, a platform is likely to want to carry out its own review of a report about problematic behaviour.

This means having a person look at the report and take a decision on whether or not it breaks the platform’s rules, and, if so, what sanction should be applied.

Platforms may need to refer some cases to an external body for review, for example if the claim is that someone is an illegal participant in an election then this may require a determination by the relevant electoral regulator.

For certain types of content, platforms may feel that they can rely on automated systems to stand in the place of a reviewer and make decisions about the content.

To support a case for automated review, platforms should be able to demonstrate that the risk of error is very low and explain their rationale for preferring this method.

In the example plan, the platform explains that all incoming user reports will be checked to see whether the refer to child sexual abuse images.

It also highlights the challenges for manual reviewers of this kind of content and describes how it has shared with the regulator details of what it is doing to support staff engaged in this work.

The platform states its clear preference for automated review of the content covered by this plan and describes its reasons for this.

This is the case with known child sexual abuse images where any instance of reported content will be violating if it matches content in the database.

A manual review adds no value in these cases and comes at a human cost to the reviewers who have to look at the material.

For other content types like hate speech, the argument is more likely to tilt towards manual review as specific forms of language may be permitted or violating depending on contextual factors.

So, a hate speech plan might express a general preference for manual review while describing some exceptions where it believes automated review can be safely used (with supporting data).

The example plan explains the particular rules that apply to child abuse images where these must be referred by law for an external review that is additional to the review carried out by the platform.

This is an atypical situation reflecting the importance that lawmakers have placed on prosecuting offences related to child abuse.

In this case the platform is carrying out an automated review that will lead to platform sanctions before referring the content out to the external body.

We might see a different model in a misinformation plan where the platform refers content out before applying sanctions which will be based on the outcome of the external review.

We may also see other laws creating duties to send material for external review and these would need to be incorporated into harm reduction plans.

Action

The plan should explain the framework for the actions a platform will take when it has found a harmful behaviour has occurred.

This will usually involve a set of graduated sanctions from restricting or removing the specific item of content through to restricting or removing the user’s access to the platform.

The most serious sanction a platform can impose unilaterally is removal of the user account, perhaps accompanied by technical measures to try and prevent re-registration.

In some situations, the risk of harm may be serious enough for the platform to refer the user out to external agencies who can take further steps, for example by initiating a criminal prosecution.

In this plan, the platform explains that it is following a ‘one strike and you’re out’ model reflecting the seriousness of the offence.

For other types of harm, we might expect to see them explain how they apply different sanctions depending on the nature of the behaviour, and then scale these up for repeat offences.

Platforms would describe the criteria for them to refer a harm out for potential criminal prosecution in this section, which the law exceptionally makes an automatic process in the case of child sexual abuse images.

Focused Plans

When people are drawing up harm reduction plans, they may feel they need to include a wide range of behaviours which relate to each other.

If we are to keep plans specific and actionable then it would be better to spawn a new plan for related issues rather than trying to cover too much in one go.

Plans can help with signposting by indicating where related issues exist and linking to the plans that deal with these.

In the example, I have identified two related areas that we know are problems but may require different treatment from the harm covered in this plan.

First, there is the question of images of children that can legitimately be shared in some contexts, but may also appear in very problematic settings.

Platforms should explain how they are responding to this harm, if it is present on their services, but would need a different set of tools to deal with this.

There is also a broader societal debate about how to deal with teenagers sharing sexual images with each other.

This situation is rendered complex by the fact that young people can be both perpetrator and victim in a particular set of communications.

A separate harm reduction plan would allow a platform to explain any particular measures it is taking to meet its duty of care towards teenagers found engaging in this activity through its service.

Next Steps

We do not need to wait for legislation to be completed for harm reduction plans to exist – platforms could start producing documents along these lines this at any time.

We need legislation to empower a regulator to oversee platforms on our behalf but plans like these would also help us form our own views about whether or not platforms are doing a good job.

With this kind of information, we can make better decisions about whether we want to use particular services or recommend them to our families and friends.

A lot of the information is already there in various policies, reports and announcements that platforms produce about what they are doing to protect users, but this can be hard even for experts to navigate.

I am sure there will be aspects of the model I have described here that people will disagree with or think could be done better – it is a beta and should be tested and improved.

I hope there will more of a consensus around the core proposition that we would all be well served – people, platforms and regulators alike – by having clear and consistent explanations of what is being done to address specific harms as a foundation for discussing whether this is effective.